‘My first reaction when I saw the photo was, ‘No way, this is definitely Photoshopped,’ says tourism worker

Behold.

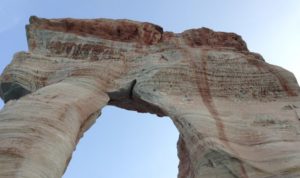

A massive, pants-like rock formation, standing tall and glorious in a pool of salt water in Canada’s Arctic.

The Nunavut community of Arctic Bay calls it “Qarlinngua” — pronounced “kar-ling-wah,” which means “like pants” in Inuktitut.

You probably can’t find much about it on Google, beyond photos posted to CBC North’s Facebook pages.

And not many people have seen it in person, according to our investigation.

CBC North received this photo from a local hunter from Arctic Bay back in August, and shared it with the world.

But the internet thought it was fake; CBC even got a typo report on it.

“Any provenance for that? Anything that big and spectacular should be a Natural Wonder of the World, but Googling reveals only THAT picture of it,” a reader wrote back in December.

“It looks like a fake photo to me.”

CBC reached out to the tourism office in Iqaluit to verify the photo, and got a similar response.

“My first reaction when I saw the photo was, ‘No way, this is definitely Photoshopped.’ I definitely thought it was fake,” said Sarah Demeester, an information counsellor with the Unikkaarvik Visitor Centre.

“And also, I just wondered why I had never heard of such an amazing formation before.”

She said there was a buzz around the office as colleagues discussed the validity of the photo. Demeester said after reaching out to her local sources, she was able to confirm the arch exists.

‘I haven’t seen anything like this in the Arctic, despite my widespread fieldwork.’

– John England, professor at University of Alberta

“[It’s] really just amazing. It kind of emphasized to me how remote we are in this part of the world up in Nunavut — the fact that something so amazing can exist … and hardly any people have laid their eyes on it in person.”

Where is it?

The Qarlinngua is located in an uninhabited area of the Brodeur Peninsula on the north end of Baffin Island, about 80 to 90 kilometres southwest of the community of Arctic Bay, according to Max Kalluk, the hunter who submitted the photo to CBC North.

The arch is only reachable by boat. It’s a four- to five-hour ride from Arctic Bay.

And there’s only a small window during the year when the summer sea ice is broken up enough to get there, Kalluk said.

“I can see why it’s considered fake because it’s very phenomenal.”

Kalluk said he was around 12 years old when he first saw the formation, passing by with his family while they were out hunting for seals.

“We get to see it every year, going to our destination where we narwhal hunt,” he said.

He estimates it stands more than 50 metres tall.

“Kind of makes you feel like small or humble, seeing something like that,” he said. “And makes you appreciate and feel privileged that you get to see this.”

A rocky cliff with similar layering serves as the Qarlinngua’s backdrop. Kalluk said there are more unique formations in the area, including one that looks like an elephant, just five minutes away by boat.

How was it formed?

Four geologists from across Canada examined the Qarlinngua photos.

“I haven’t seen anything like this in the Arctic, despite my widespread fieldwork,” said John England, a professor emeritus at the University of Alberta’s earth sciences department, who’s done research throughout Canada’s Arctic for 50 years.

He said the scientific name for it is a sea arch, or a natural arch.

The scientific name for this formation is a sea arch, or a natural arch. It’s created through erosion over time. (Max Kalluk)

England explained that most coastlines in the Arctic are still rising from the sea due to “the unloading of the crust” by the ice sheets that melted away about 10,000 years ago, gradually moving the coastline away from the cliff. But there are also areas where the land is sinking relative to the sea.

“So, in these areas,” he said, “likely like where your photo was taken, the sea is now rising faster than the land, and if there’s a lot of open water in the summer, the sea is eroding into a nearby cliff, whose coastline is slowly sinking.”

A combination of wind and water would erode cliff rocks over many years, forming isolated sea arches. The horizontal layers in the Qarlinngua indicate it is sedimentary rock, or sandstone, which is good erodible material.

The portion that’s still standing likely contains a large volume of quartz, which is resistant to erosion, said Linda Ham, chief geologist with the Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office.

Ham also confirmed she and her fellow geologists in the office in Iqaluit have never seen anything like the formation anywhere in the Arctic.

“Because up here, [we have a] very, very hostile environment,” said Ham, who explained it’s more common to see natural formations like these farther south in places like Alberta, Utah or the Oregon coast.

Ham said the rocks in the Brodeur Peninsula area are Paleozoic rocks, meaning they’re around 250 to 600 million years old.

England said until recently, most of the coastlines in the Arctic had been dominated by summer sea ice, which would allow for a slower erosion of formations such as the Qarlinngua.

More open water could speed up the process.

England estimated the Qarlinngua could collapse and disappear in a matter of decades, while other geologists who spoke with CBC News said it could take thousands of years.

But they said the cliff behind the Qarlinngua will also erode, so it’s possible several new arches will form.

‘A land of opportunities’

Arctic Bay Adventures confirmed it’s the only tour company that takes people to the Qarlinngua.

Manager Gene O’Donnell said he’s taken several groups of tourists to the formation in the past three years. He said the company plans to advertise the tour on its website soon.

“It’s like a monument to something. I’m not sure what it is,” O’Donnell said. “I think it’s something sacred.”

Nunavut’s tourism director says she was unaware of the Qarlinngua and is excited to start promoting it. (Submitted by Max Kalluk)

The challenge, O’Donnell said, is the very limited window when the formation is accessible — last year it was just a week; the two years prior it was 13 days.

“It’s fantastic. It’s phenomenal,” said Nancy Guyon, Nunavut’s director of tourism and cultural industries.

She, too, was unaware of the formation until CBC asked for comment.

She said the government’s tourism department will soon hold meetings on the Qarlinngua and hopes to promote it to its target tourism clients: high-income travellers aged 45 and up. It can cost around $2,000 for a one-way flight from Iqaluit to Arctic Bay.

“Nunavut has so many gems like this,” Guyon said.

“I’m always calling it a land of opportunities.”