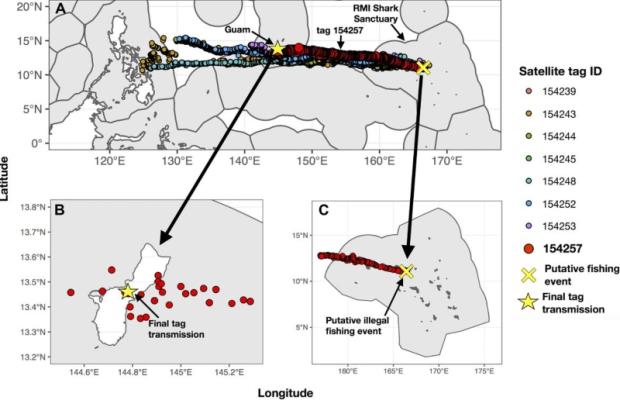

Conservationists were eager to track grey reef sharks’ as they swam across a protected shark sanctuary in the South Pacific. Excited researchers watched the movements of tagged sharks leaving the Marshall Island’s Bikini Atoll. Suddenly, eight tags were beelining across the ocean toward the island of Guam.

The scientists thought they had stumbled across some unknown migration. “Nope,” movement ecologist Darcy Bradley, told them. “Your tags are on boats.”

Technology is helping ships find and extract ever-larger quantities of ocean life for human consumption. Now it’s also being used to stop it. Bradley, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California Santa Barbara, said the South Pacific researchers were too late. Bradley had informed authorities, but by then the illegal fishing boats nabbing grey sharks in the sanctuary (commercial sharks fishing is banned within an area covering more than 2 million square kilometers) were already thousands of kilometers away.

That wasn’t the case in Europe this month when police caught 79 suspected tuna smugglers through Operation Tarantelo. Europol says it used the traffickers’ tablets, phones, GPS devices, and catch records to track down 80,000 kg (88 tons) of illegal bluefin tuna. Law enforcement agencies in Span, Portugal, and Italy uncovered false papers, fake boat bottoms, and a massive smuggling ring to bring the fish to market.

Money in illegal seafood is massive. In Europe, the volume of illicit bluefin tuna sold last year was double the annual legal trade, which is estimated to be around 1.25 million kg (1,377 tons), according to Europol. The profits are larger too. Illegal fishing is the world’s sixth most valuable crime, reports the non-profit Global Financial Integrity). That was illustrated by Operation Tarantelo’s confiscation of US$576,000 in cash and seven luxury vehicles. And that’s only one species. Overall, nearly a quarter of seafood humans catch each year is fished illegally.

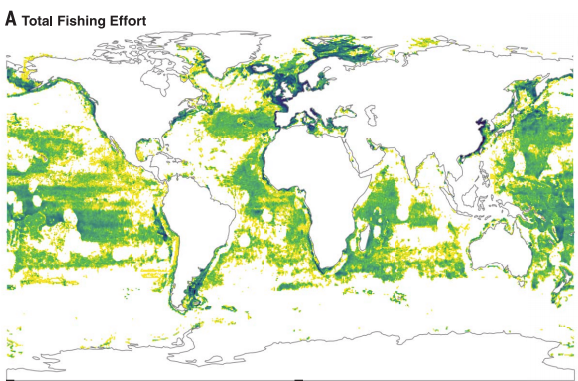

What can be done about it? One of the major problems is keeping track of illegal vessels. “Mother ships,” or enormous fishing vessels that may stay at sea for years, can offload illegal catches onto other boats, which sell the harvest at distant harbors. Satellites and automatic identification system (AIS) tracking devices are now being repurposed to monitor fishing effort. AIS devices, originally designed to avoid ship collisions, send back signals to reveal a ship’s location, identity, and speed. A recent study published in Science (paywall) analyzed AIS messages from more than 70,000 industrial fishing vessels between 2012 to 2016. The data showed the scale of the industry that must be tracked over at least 55% of ocean, an area four times larger than agriculture. Of course, many illegal vessels aren’t tracked at all.

But safe harbors must also be eliminated. Europe has among the strictest controls in place to track landings of seafood. Irregularities in production numbers were the first sign that tipped off authorities to the illegal tuna ring. No such tracking regime exists in countries like China and the Philippines, where many officials may be willing to look the other way. The spread of high seas fishing, which takes place outside of individual nations’ economic zones is where many illegal fishing fleets operate. High seas fishing is dominated by just five countries, Smithsonian reports: China, Spain, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea. Their cooperation will be needed to reign in illegal operations.

There are signs that things are changing. An international effort is underway to enforce a “legal, sustainable, and transparent” tuna supply chain by 2020. Indonesia recently banned foreign fishing fleets and transshipment at sea, forcing boats to return to port to offload catches. That constrained tuna supplies by nearly doubling the price of some species, primarily yellowfin tuna and skipjack tuna, in local markets according to Singapore’s Straits Times.

Whether Indonesia will manage its resources to sustain them into the future or merely shift overfishing practices to local fleets remains to be seen.