Carl Lutz was initially reprimanded for his actions; Holocaust survivors in Canada want him honoured

On New Year’s Eve 1944, six-year-old Andras Spiegel watched as Nazi troops stormed the former glass factory where he, his parents and 2,000 other Jews had taken shelter in Budapest, Hungary.

They were all marched outside, lined up and told to hold their hands in the air. They stayed there for three hours until a man in a foreign diplomat’s car arrived. The man argued with the soldiers and soon Spiegel and the others were allowed back inside, but not before some had been killed. Spiegel, who is now known as Andrew Simon, recalled seeing three dead bodies.

“And what I know now, what I didn’t know then, is that we were about to be marched to the Danube [River] to be shot because they had no other way of getting rid of us,” Spiegel, now 80 years old, said in an interview.

Spiegel and his family survived the Nazi occupation and in 1950 escaped what was by then Communist Hungary by “sneaking through a barbed wire fence at night with the aid of a generously bribed border patrol officer” and enter ed Austria, he said.

Once in Canada, Spiegel became Simon. He spent most of his working life at the CBC in radio and television. He was the founding producer of the radio program Cross Country Checkup.

He wants more recognition for the man he believes saved his life — and the lives of tens of thousands of others.

“I thank him for my own life and my parents’ lives. All the thousands of Jews he saved,” he said at his home in suburban Toronto.

‘Swiss Schindler’

That man was Carl Lutz. Known informally by some as the Swiss Schindler, Lutz was the diplomat who arrived on the scene in Budapest and ensured Simon and others were not killed that night.

Historical accounts credit Lutz with saving between 40,000 and 60,000 Jews.

Yet unlike German businessman Oskar Schindler, whose heroism was depicted in the Oscar-winning film Schindler’s List directed by Steven Spielberg, or Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who was given honorary Canadian citizenship for his role in saving Jewish lives, Lutz has remained relatively little known.

A room was named in Lutz’s honour in a palace in Bern. But for some survivors, it is not nearly enough recognition.

Survivor testimonies

A new book, Under Swiss Protection, includes testimonies from some of those who survived because of Lutz’s actions. The book was edited by University of Victoria professor Charlotte Schallié and Lutz’s daughter, Agnes Hirschi.

There have been other accounts of Lutz’s actions through the years, including one from Yad Vashem, the Holocaust remembrance centre in Israel. Upon declaring Lutz “righteous among the nations” in 1964, it noted he had risked his life many times and that is actions jeopardized his diplomatic career.

By 1944, the Nazis had surrounded Budapest, working in co-operation with Hungarian troops known as the Arrow Cross, who were loyal to Adolf Hitler.

As a boy, Simon saw and heard the bombings. He and his friends tried to make a game of it.

“We would stand on the balcony and watch the skies to see if there were any enemy planes and scream, ‘Air raid,'” he said. “We thought it was a big gag. It was fun to run down to the air-raid shelter.”

But the attacks, both from the air and on the streets, intensified. That’s when Lutz stepped in — without orders from Switzerland.

According to the new book, Lutz, who was vice-consul and head of the foreign interests division in the Swiss legation in Budapest, led a risky operation to save Jews between March 1944 and February 1945.

Co-editor Schallié, who specializes in Holocaust education, has tried to uncover why this quiet bureaucrat would take on such a mission.

“He was a deeply religious man,” she said in an interview. “But he was also a great humanitarian. And so I think it was a combination of deep sense of justice and a deep religious commitment.”

Negotiations with Nazis

By October 1944, Budapest was seeing repeated raids on Jewish homes and executions on the banks of the Danube before bodies were dumped in the river.

Lutz negotiated with the Nazis, including Adolf Eichmann, a high-ranking Nazi official and member of the SS who oversaw the rounding up and deportation of Jews in Hungary and elsewhere to death camps. He obtained authorization to issue “protective letters” that gave the individuals named within them permission to emigrate.

It was, according to the book, a legal ruse. Lutz only had authorization for 7,000 individuals but expanded the protection to entire families. He is said to have issued 50,000 such documents.

Lutz then persuaded authorities in Hungary to let the holders of the letters move into special safehouses where residents had diplomatic immunity, according to the book.

Inside the Glass House

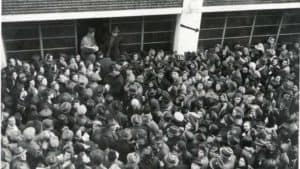

One of them, an old glass factory known as the Glass House, became the largest Swiss-protected safehouse in the city.

It’s where Simon turned up with his mother in the fall of 1944.

“I go with her, and she knocked on the door and said, ‘Please let us in because my child and I need protection, and we are Jewish,'” he said. “Initially, they didn’t let us in because they said it was overcrowded. She somehow persuaded them.”

Conditions inside were horrendous, according to another survivor, Gabor Maté, a physician who now lives in Vancouver.

“You can imagine toilet facilities were completely overwhelmed,” he said. “There were feces and manure on the floor. Food was very uncertain. A lot of disease.”

Maté was not yet one year old when he and his mother entered the Glass House. She kept a diary and told him about their lives in later years after they, too, escaped to Canada.

Even with the protection offered by the Glass House, Maté said his mother fell into despair as he became sickly. She already knew her parents had been killed in a death camp and her husband was in a labour camp.

“My mother decided to actually give me away because she didn’t think she could guarantee her life let alone mine,” he said. “And so she handed me to a passing Christian woman on the street and said, ‘Please get him out of here.'”

The woman delivered Maté to his mother’s relatives, who were in hiding underground and therefore less likely to be caught, he said.

Maté and his mother were reunited after the Glass House was liberated on Jan. 18, 1945. His family eventually escaped Hungary and moved to Canada.

Maté, 74, is one of Canada’s leading authorities on childhood trauma and addiction. He has no doubt his choice of work is linked to what he experienced in Budapest.

He also has no doubt Lutz is a hero.

“I want to say thank you,” he said. “I can’t imagine where you found the resourcefulness and the sheer wit and the sheer chutzpah, the sheer guts.”

Maté said the Canadian government should give Lutz honorary citizenship, as it did to Wallenberg.

“Certainly, Carl Lutz belongs in the same ranks,” he said.

‘It was a most dangerous and difficult task’

Lutz died in Bern, Switzerland, in 1975.

In the new book, there is a copy of a letter he wrote in 1970. It is one of the few times he shared any insight into what he did in Budapest. By that time, word had spread that he was struggling financially.

“I feel sorry that I could not save more of my fellow beings,” Lutz wrote to one couple who sent him $50 US with their thanks. “But it was a most dangerous and difficult task to negociate (sic) with SS. Eichmann as I did.”

In February, the Swiss government formally honoured Lutz’s memory by naming a room in the Swiss Federal Palace in Bern after him.

But Switzerland initially reprimanded Lutz for taking the actions he did.

That still bothers Simon.

“This guy was a great man,” he said. “We should never forget his name.”