The technology sector has reigned supreme over the last year. With sectorwide returns of 24%, it outperformed the next best sector, industrial goods, by 10 percentage points.

But within tech, it’s the rise of cloud computing that’s stolen the spotlight.

Cloud computing uses remote servers to store, deliver, and manage data and applications over the Internet. It eliminates the need for local servers and oftentimes the cumbersome installation involving an IT department.

Over the last year, the largest pure-play cloud companies have left the Nasdaq behind. The slowest-growing of that group has more than doubled the tech industry barometer; the fastest has quintupled the index’s returns:

So what’s been driving cloud company stocks ever higher? And can it continue? Let’s take a closer look.

For starters, the wave of enthusiasm for tech stocks in general has provided a tailwind. Consider that today, the four largest companies in the world are all tech: Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, and Microsoft. Each of these is invested in the cloud, too, but largely through storage; none of them are pure cloud businesses. This differs from the software-as-a-service companies that I would consider pure-play cloud companies.

The biggest players solely focused on the cloud are the ones shown below, in order of market capitalization:

Cloud Company Market Cap

Salesforce (NYSE: CRM) $89.7 billion

ServiceNow (NYSE: NOW) $29.8 billion

Workday (NASDAQ: WDAY) $28.5 billion

Shopify (NYSE: SHOP) $14.1 billion

Atlassian (NASDAQ: TEAM) $13.7 billion

There are three reasons these companies have seen their market caps balloon recently, and here’s what they boil down to.

1. Eye-popping growth rates that stick

Cloud companies have tremendous advantages over companies that make physical things or provide high-touch services. When software is packaged as a service (SaaS), it can be rolled out to customers incredibly quickly. It can require minimal direction interaction with users. Early on in the life of a SaaS company, sales growth rates of 70%, 80%, even up to 100% are not unheard of.

The cloud-based commerce platform Shopify, for example, has a five-year average annual sales growth rate of 95%. Shopify provides a suite of products that helps primarily small-to-medium businesses connect potential customers to their merchandise online and through social media.

While we’ve witnessed these growth rates before — like during the early 2000s for Salesforce — what we’re seeing for the first time is how sustainable some unusually high growth rates can be in the cloud. Salesforce today is a 19-year-old company. Yet its average annual sales growth rate over the last five years has been 30%. If that were to persist, sales would double in roughly 2.5 years.

A $10 billion company like Salesforce doubling sales in less than a few years is hard to wrap your head around. But Salesforce — even at its size — is all about speed.

It has a lock on big clients because it makes their sales teams more effective while minimizing IT upgrades. Salesforce’s cloud creates a seamless connection between salespeople and key corporate decision-makers. Its products can better anticipate needs though a data-driven feedback loop and introduce customers to new products as their businesses change. This short cycle is unique to the cloud, it compounds over time, and it’s a key reason the market’s willing to pay up for shares.

2. High switching costs and network effects

Cloud businesses are capable of ramping up new users in a hurry. And they’re increasingly finding ways to ingrain these users with their products. The type of user will depend on the cloud business: Salesforce tends to serve businesses, whereas a cloud business like Intuit’s serves individuals.

Users of all sizes can be more quickly integrated into an ecosystem in recent years due to the rise of one key tool: application programming interfacing, or “APIs.” If it sounds complex, it’s not. What APIs do is facilitate communication between data sources and software.

When software can rapidly be integrated, customers get more functionality. It also allows the cloud business to collect more data on, say, your financial habits. As a result, two effects occur: the more users, the better the data; and the more integration, the more embedded the users become. These things build on one another rapidly. This is how cloud companies build what investors call an “economic moat” at a pace we’ve never seen before.

In this case, the economic moat consists of high switching costs and data-driven network effects. Again, investors look at a cloud business and see how fast it’s growing and that its business is becoming more durable by the day. Paying 10 times sales doesn’t seem that ridiculous.

3. Rapid ecosystem creation

Building on the above, growth of a single and highly functional product is not sufficient in this market. Cloud companies are adding products in rapid-fire fashion — building an ecosystem of products in a handful of years, a process that used to take decades.

Apple’s ecosystem took years to create. The iPod came out in 2001, the iPhone debuted six years later, and then the iPad took another three years. Building an ecosystem of physical products takes time. Of course, Apple is also a software company, so it was hooking users into its universe in that way, too.

Cloud companies have proved that they can both acquire and build products rapidly. And they can take a user from uninitiated to ingrained rapidly, too. Think of a new Intuit customer going from Mint to QuickBooks Online to TurboTax (all Intuit products) in the course of a single tax season.

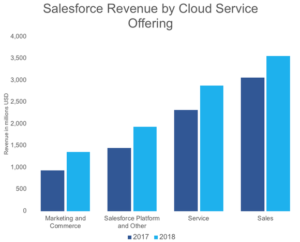

Salesforce can perform the same feat at an enterprise level, so its suite of $1-billion-plus clouds has now grown to four:

Investors see the creation of an ecosystem and think of the success that companies like Alphabet and Apple have had with theirs. That’s a long-term trend that makes the market salivate, only now it occurs at an even faster pace.

The ascension of the cloud

This is a unique time for companies running cloud-only businesses. The first reason they’re soaring is their growth rates — primarily in new users and sales. Earnings, in fact, are usually scarce early on in a cloud business’s existence.

But their success will depend on the No. 2 and No. 3 reasons listed above. Whether long-term investors should be willing to pay up for a given cloud business should come down to signs of an emerging economic moat. High switching costs and network effects could be worth a premium. Those companies without them could fall as quickly as they rise.