‘Life-changing’ exchange helped save young man, but for nearly 15 people a year, the story ends differently

The subway platform at Dundas station was packed with commuters like any typical Wednesday when John Paul Attard noticed a man walk by and then lower himself onto the tracks.

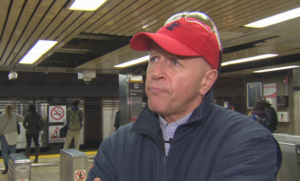

Attard, a Toronto Transit Commission collector, says his intuition kicked into gear immediately. Within seconds, he had the TTC cut power to the station.

Attard called transit control and then did something thousands of people have since seen in an online video that has made the rounds on social media.

Amid all the bustle, he quietly sat down at the edge of the platform and looked into the man’s eyes.

“I said to him, ‘Are you having a bad day?'” Attard said. “He says, ‘Yes, I want to hurt myself.’ That’s when I just kind of embraced him and hugged him.”

Around 15 people killed each year

“Let me hold you,” Attard said. They began to talk and the conversation spanned from the future to hip hop music and what the future holds.

“I will be your mentor, I will take care of you,” Attard told the man. “I was putting affirmations in his mind to take him from negative to positive.”

Through the April 26 exchange, which lasted about 20 minutes, Attard managed to talk the man, who he says was 23 — young enough to be his son — back from the brink of suicide.

According to the TTC, some 20 to 30 people jump in front of subway trains each year, ending the lives of about half of them.

The transit commission would not specify the locations or days of the week when suicides occur on the subway system. Spokesperson Stuart Green said in an email to CBC Toronto: “These unfortunate incidents can happen at any time.”

Green said suicide prevention is something the transit agency takes seriously.

So seriously, in fact, that frontline personnel are trained on what to look for in someone contemplating suicide on the subway through what the TTC calls “the gatekeeper program.”

Tragedy ‘extends beyond the individual’

Earlier this year, spokesperson Brad Ross acknowledged suicides were also linked to absenteeism within the agency — especially among subway operators.

Green agrees.

“The tragedy of someone losing their life or being severely and permanently injured extends beyond the individual and his or her family. The train crew, witnesses and other TTC personnel involved in suicide incidents face possible life-altering, post-traumatic stress disorder.”

That’s something Attard, who says he grapples every day with his own mental illness, has seen first-hand.

Attard says he has lost three fellow TTC employees to suicide over his 24-year career with the agency.

Green declined to disclose the number of employees who have died from suicide and would not comment on how job stress might contribute to such cases.

As for suicides on its subway platforms, Green confirmed that barriers in the form of platform-edge doors have been discussed, but there is no timeline or funding commitment. The agency gave in-principle approval to the barriers in 2010, but to date they have not been implemented in the cash-strapped system.

“It’s a very expensive proposition,” Green said.

But while barriers may still be years away, Dr. Katy Kamkar, a clinical psychologist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, says moments, such as the one in which Attard found himself last Wednesday, can play a powerful role in breaking the stigma around mental health issues.

Social media and mental illness

“I think social media has been helpful in terms of helping — opening up the dialogue and the conversation around mental health and mental illness … And here’s a situation where someone approaches someone who was in distress, listens to the person, providing listening, providing the support and care, and it made all the difference,” she said.

While there has been some improvement in taking the stigma out of mental illness over the past five to 10 years, Kamkar says, much could be improved.

She says if instances like Wednesday’s can prompt discussion around mental health and normalize the conversation using positive and health messages, they can play a crucial role.

She says 70 per cent of mental health and addiction problems begin in childhood and adolescence, with people between ages 15 and 24 reporting the highest level among any other age group.

“Everyone might react to it differently depending on their history. For some people, it could be a trigger. For some others, they might see it a different way,” said Kamkar.

“But I think it really speaks to the notion of a human being helping another human being … that human touch, which is so important.”

Over the course of those 20 minutes on the track, Attard says he could eventually see light in the face of the man on the tracks.

Moment was ‘life-changing’

“I put my hands on his temples and had him repeat, ‘I am strong, I am strong.'”

In an unforgettable moment, he asked others to join in. Soon, virtually everyone on the north and southbound platforms could be heard repeating the phrase in one resounding voice.

As police and paramedics arrived, Attard continued speaking to the man, whispering: “You are going to be OK, I’m going to be your mentor, I’m going to be your friend.”

It was, as Green put it, an “act of compassion for a person in distress.” He says it’s a testament to the acts of kindness that transit employees carry out every day.

“Some, like this one, are life-changing.”

Where to get help

Kids Help Phone – 1-800-668-6868 (Phone), Live Chat (online chat counselling) — visit www.kidshelpphone.ca

Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention: Find a 24-hour crisis centre

Health Canada’s toll-free number for the First Nations and Inuit Hope for Wellness Help Line is 1-855-242-3310.

If you’re worried someone you know may be at risk of suicide, you should talk to them, says the Canadian Association of Suicide Prevention. Here are some warning signs:

- Suicidal thoughts.

- Substance abuse.

- Purposelessness.

- Anxiety.

- Feeling trapped.

- Hopelessness and helplessness.

- Withdrawal.

- Anger.

- Recklessness.

- Mood changes.