Even Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi is hesitant about the ride-hailing company’s goals to have a flying taxi service airborne in five years.

At the second day of the Uber Elevate Summit, Khosrowshahi spoke about UberAir, the company’s electric vertical take-off and landing (e-VTOLs) aircraft flight-sharing network, or flying taxis.

While optimistic that electric four-seater crafts flown by a pilot will soon be possible, and that UberAir will certainly hit its 2020 goal for demo flights in Los Angeles and the Dallas area, Khosrowshahi said he had to be convinced that the cost would come down, and that the service would be accessible to the masses or even residents of those two cities by 2023.

“There’s a lot that has to come together,” he told Bloomberg journalist Brad Stone on the Los Angeles stage.

Just like Uber doesn’t want to build and maintain cars for its streetside ride service, UberAir is partnering with companies like Embraer, Bell, Aurora Flight Sciences, Pipistrel Aircraft and Karem to build and maintain its design of a craft that can fly 60 miles on a single battery charge at an altitude of about 1,000 feet.

“What I think is truly different,” Khosrowshahi said, “is building this to not be a service for the few, but a service that is ultimately available for mass market.”

Uber basically wants to bring UberPool shared rides to the sky — with prices that don’t exclude certain passengers. Getting to that point seems tricky, especially with technical limitations, regulatory hurdles, and high costs for everyone: Uber, its partners, cities, and customers. Khosrowshahi called that the “real challenge,” and he already knows Uber will lose money to launch the flying service.

“We’ll take short-term losses in order to build the company,” he said. But although they might be short-term, these could be massive losses resulting from costly equipment, research, infrastructure, pilots and staffing. One day, the planes will be autonomous, but until then it won’t be as easy to hire Uber pilots as Uber drivers.

Plus, Uber’s aggressive business approach on the road won’t work up in the sky. “Aviation is a different ballgame and we gotta play by the rules,” Khosrowshahi said.

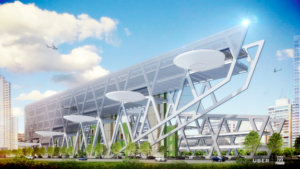

A look at six final designs for UberAir’s skyports, dreamt up by architecture firms, shows how fantastic and far off the reality of Uber in the sky really is, even if the team is working with the Federal Aviation Administration and NASA.

“I think the ideas look pretty freaking awesome,” Khosrowshahi said.

But massive infrastructure changes in cities don’t happen overnight, and Khosrowshahi knows that. “We’ve got to think about the scale of these things,” he said.

The six final concepts of skyports, where flying taxis could pick up and drop off passengers in different cities, hold blue-sky goals to build facilities within a 3-acre footprint near stadiums, train stations, concert halls, airports or other busy areas. These look appealing, but are pure fantasy, especially when they have to be built in many locations to make UberAir possible. The flights only go short distances and are intended to be accessible and efficient.

The skyports also need to function as a charging spot for the vehicles, all while following noise and environmental rules. It’s a lot, and while it looks great and futuristic, Uber has spent the past two days trying to convince everyone this is possible, somehow, some way, and soon.

UberAir’s slogan is “Closer than you think,” aiming to really bring the point home that this can happen — and soon.

“I came here because this is a company that will change the world,” Khosrowshahi said during his conversation about UberAir. But it may take a long time for that world-changing to happen, especially if the FAA is involved.