The annual income of older Americans could drop significantly from one year to the next for a variety of reasons. It might be retirement or the death of a spouse, perhaps, or the sale of a business.

Yet it might take Medicare — which charges higher earners more for premiums — a couple years to adjust when income falls below the threshold.

If you’re paying more than the standard amounts for Medicare Part B (outpatient services) and Part D (prescription drugs) through so-called income-related monthly adjustment amounts, or IRMAAs, the difference can reach into the hundreds of dollars per month. And, the surcharge is often based on your tax return from two years prior — which may not accurately reflect your current financial situation.

“We see it all the time,” said Danielle Roberts, co-founder of insurance firm Boomer Benefits in Fort Worth, Texas. “They end up having to contact Social Security and show they’re not earning that amount anymore.”

Of Medicare’s 62 million beneficiaries, about 7% — 4.3 million people — pay those monthly surcharges, due to various legislative changes over the years that have required higher-earners to pay a greater share of the program’s costs.

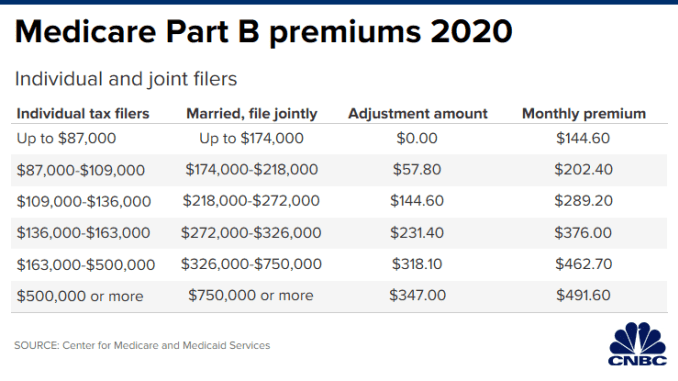

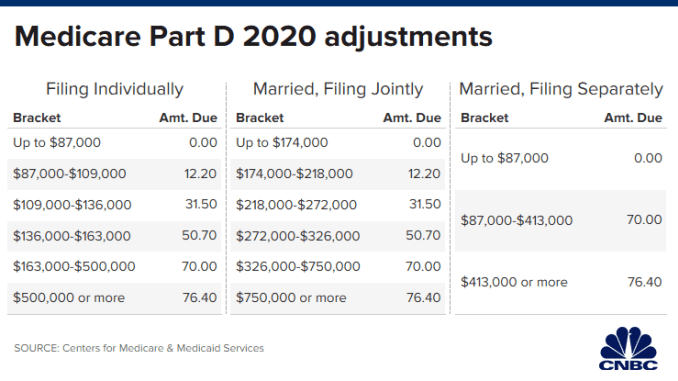

For individuals, IRMAAs kick in if your modified adjusted gross income is more than $87,000; for married couples filing joint tax returns, they start above $174,000.

The standard monthly premium for Part B this year is $144.60, which is what most Medicare beneficiaries pay. (Part A, which is for hospital coverage, typically comes with no premium.) The surcharge for higher earners is from $57.80 to $347, depending on income. That results in premiums ranging from $202.40 to $491.60.

For Part D, the surcharges range from $12.20 to $76.40. That’s in addition to any premium you pay, whether through a standalone prescription drug plan or through an Advantage Plan, which typically includes Part D coverage. While the premiums vary for prescription coverage, the average for 2020 is about $42.

As mentioned, the Social Security Administration relies on your most recently filed tax return — which often is from two years prior — when determining whether you’ll be charged the extra amounts. In other words, for 2020, that would have meant your 2018 tax return was used.

“They did the adjustment late last year and, at that point, they only had your 2018 tax return because you hadn’t prepared your 2019 return yet,” explained Roger Luchene, a Medicare agent with Hammer Financial Group in Schererville, Indiana.

The process to prove that your current income is lower involves asking the agency (either over the phone or in writing) to reconsider their assessment. You also have to fill out a form and provide supporting documents. While it depends on your situation, suitable proof may include a more recent tax return, a letter from your former employer stating that you retired, more recent pay stubs or something similar showing evidence that your income has dropped.

The required form includes a list of “life-changing” events that qualify as reasons for reducing or eliminating the IRMAAs, including marriage, death of a spouse, divorce, loss of pension or the fact that you stopped working or reduced your hours.

As long as you meet one of the qualifying reasons, “most of the time it gets adjusted,” said Elizabeth Gavino, founder of Lewin & Gavino in New York and an independent broker and general agent for Medicare plans.

If it doesn’t, you can appeal the decision to an administrative law judge, although the process could take time and you’d continue paying those surcharges in the meantime, Roberts said.

Additionally, the SSA reevaluates your situation every year, which means the IRMAAs (or whether you pay them) could change annually, depending on how volatile your income is.

Roberts said she’s seen some Medicare beneficiaries who take no medications simply decide to not sign up for coverage, in order to avoid paying so much for a Part D plan that they think they’ll never use.

Be aware, however, that the decision could leave you financially vulnerable if your long-term health unexpectedly changes or a one-time health event requires prescription drugs. You also could face late-enrollment penalties, as well, if you don’t qualify for an exception. (The same goes for enrolling late in Part B.)

“You’d be caught without coverage and have to pay out of pocket,” Roberts said. “And, you’d have to wait until the next [enrollment] period to get into a plan.”