Retirees need to guard against tricks played with performance numbers

The stock market is about to look a heck of a lot more attractive.

But it won’t be because publicly traded corporations have become a lot more profitable, or for any of the other standard reasons why equities might legitimately become more attractive.

On the contrary, the soon-to-be-more-attractive stock market will derive from what is little more than a statistical sleight of hand. Retirees need to be on their guard so that they don’t become seduced by it into increasing their equity exposure for the wrong reason.

What will soon happen is that the worst months of the financial crisis will disappear from the trailing 10-year performance period. What that means: Even if the stock market goes nowhere over the next six months, its trailing 10-year return will nearly double.

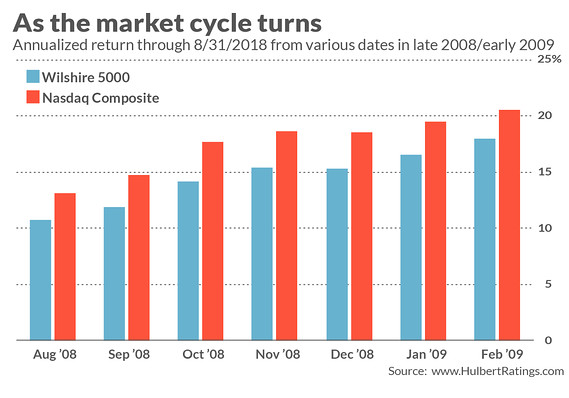

This is illustrated in the accompanying chart. For the 10 years through Aug. 31 of this year, the Wilshire 5000 index W5000FLT, -0.15% produced a 10.7% annualized return. Even if the stock market next March is at exactly the same level as it is today, the 10-year return at that time will have magically increased to 18.0% annualized.

Historians among you will notice that this is almost as high as the return the Wilshire 5000 produced during the run-up to the internet bubble: For the 10 years through March 2000, just before that bubble burst, the Wilshire 5000’s annualized return was 18.5%.

Rarely in history does the passage of just a few months’ time have such a big effect on the 10-year rankings. And, yet, few advisers have even begun to take notice.

Jack Bowers, editor of the Fidelity Monitor & Insight newsletter, is one of the few who has begun to take notice. In the latest issue of his newsletter, he warned clients: “Starting next month, 10-year returns will skew progressively higher, providing an overly optimistic view of what might be possible with stock funds… over a decade… If you are using them as a guide for what might be coming down the road, consider subtracting a percentage point or two to reduce the potential for disappointment.”

One reason to pay attention to Bowers: The equity-focused model portfolios in his newsletter produced an average return of 12.4% annualized return over the last 30 years, according to the Hulbert Financial Digest, versus 10.7% annualized for the Wilshire 5000. The only other monitored newsletter that performed better over those three decades focused on picking individual stocks rather than mutual funds, and was nearly twice as risky.

My only quibble with Bowers is that I think he should have gone even further, subtracting more than just a “percentage point or two” in order not to be misled about what is realistic. Since 1926, for example, the stock market’s annualized return is 7.1% on an inflation-adjusted basis. That’s barely half the 13.5% real return of the S&P 500 SPX, -0.04% since the financial crisis.

Furthermore, the stock market over the next decade could very well turn out to produce below-average returns. As I pointed out in a recent Wall Street Journal column, the eight indicators with the best long-term track records are projecting returns over the next decade anywhere from 3.9% annualized below inflation to just 3.6% above inflation.

In your retirement planning, therefore, you at a minimum should substitute stocks’ historical average returns for what will soon emerge in the 10-year rankings. And if you find at all compelling the bearish message of the long-term indicators I refer to in my recent Wall Street Journal column, you should become even more cautious still.

To be sure, it’s entirely possible that stocks in coming years will do better than their historical average. The question for you is whether you want to bet your retirement on that possibility. It seems more prudent not to, and then be pleasantly surprised, than to bet on it and then be unpleasantly surprised and have your retirement standard of living suffer as a result.