Researchers use universe as a microscope to make historically significant discovery

Imagine walking out to your backyard, setting up a telescope, pointing it at Pluto and being able to see something the size of a flea on its surface.

That’s the equivalent of what astronomers from the University of Toronto have done.

In a new study published in Nature, researchers using data collected from the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, have observed two intense areas of radiation only 20 kilometres apart that are 6,500 light-years from Earth. It is one of the highest-resolution observations in astronomical history.And they used the universe as a microscope to do it.

The objects themselves are pretty impressive, too.

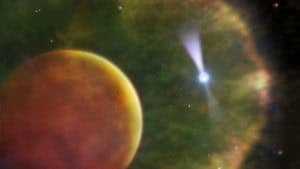

One is a star called a pulsar, which is sometimes referred to as a cosmic lighthouse. Such stars rotate rapidly — more than 600 times a second. As they do this, they emit two powerful beams of radiation from their poles outward into space.

Scientists know of roughly 2,000 pulsars and about 30 of them are eclipsed every so often. But it’s not known what’s causing the eclipse: Is it dust or another body, like a planet?

These new observations helped answer the question for one of them.

‘This can’t be right’

When examining data on the first eclipsing pulsar to be discovered, a star known as PSR B1957+20, University of Toronto PhD student Robert Main noticed that every so often, it pulsed about 100 times brighter than normal. Near the time of the eclipse, the signal went “wild.”

“I was detecting about 10 times as many of these bright pulses as I should be,” he said. “At first I thought, ‘Hm. This can’t be right.'”

But it was.

“Occasionally, the whole signal would be boosted by factors of 10 or 30 or more for many pulse rotations and then it would go away. And that happened right before and right after the pulsar was completely eclipsed.”

Basically, we used the universe as a microscope or a magnifying glass.

– Robert Main, University of Toronto

The eclipse was caused by a brown dwarf, an object that is somewhere between a star and a massive planet like Jupiter. This particular brown dwarf is about the third of a diameter of our sun, but with roughly less than two per cent its mass.

As the two entities orbit each other — once every nine hours and just two million kilometres apart — the pulsar’s strong radiation makes the brown dwarf shed its layers, creating a kind of cosmic wake behind it. In about a billion years, the brown dwarf will completely disappear and its material will be forever dispersed into space. Because of this interaction, a pulsar in this type of system is known as a “black widow.”

Main discovered that stream of shed material was causing the eclipse. It’s also what magnifies the signal.

“Basically, it’s acting exactly the same as if you were to put up an aberrated lens in front of [the pulsar], which will sometimes perfectly focus all the light to us,” Main said.

It’s akin to a pool on a sunny day: the water bends light and creates bright patterns of sunlight where all the light is focused.

Using this lensing method, the team was able to make an extremely precise measurement.

“This gives us a remarkable new tool to do measurements that are otherwise not possible on Earth,” Main said. “That’s a million times finer than you can get with telescopes on Earth.”

It may also be used as a tool for better understanding fast radio bursts (FRBs), mysterious bursts, short pulses of radiation that astronomers still don’t understand.

And the fun part is that they used the universe to learn more about the universe.

“Basically, we used the universe as a microscope or a magnifying glass,” Main said.