How researchers are solving technical, psychological challenges of getting a crew to Mars and back

It’s the kind of thing that seems doable, in a “surely-someone-will-figure-it-out” kind of way. That is, until you consider the nearly endless list of details involved.

Getting humans safely to and from Mars, long a staple of Hollywood movies, has proven to be much more easily imagined than achieved.

“Spaceflight is maybe the most dangerous thing humans have ever done,” says Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques, while preparing for his mission to the International Space Station.

“It’s risky,” he says. “It always will be.”

Saint-Jacques frames any potential journey to Mars as a risk balance, weighing the value of such a trip against the likelihood of surviving it.

“Eventually we will go to Mars, when that risk balance kind of makes sense,” he says.

It’s that same presumption that has teams from NASA plugging away trying to achieve that balance.

Martian getaway in Hawaii

Many might assume the big barriers to a successful Mars mission are all about technology, but NASA is also researching ways to deal with other crucial aspects of such a trip — the psychological ones.

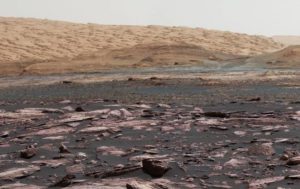

It is funding a project run by the University of Hawaii that sends volunteers to a remote, rocky, red-tinged hillside near the Mauna Loa volcano where, apart from the blue sky and scattered clouds, the vista looks, well, downright Martian.

Visitors aren’t allowed anywhere near the place.

The idea is for the volunteers to be isolated and live together inside a cramped 11-metre-wide domed habitat for eight months, as if they were actually on faraway Mars.

All communications with the rest of the world are on a time delay, as they would be on a real interplanetary expedition. Depending on how far Mars is from Earth at the time a message is sent, it can take radio signals up to 24 minutes to make the trip — each way. That can make conversations frustrating.

“The whole thing is an exercise in patience and humility,” mission volunteer Brian Ramos told CBC News.

For the crew in Hawaii, supplies arrive occasionally, but otherwise they grow their own food, fix whatever breaks, and conduct experiments.

And, wearing hermetically sealed outfits, they explore the surrounding area. Realism is key, so they’re not allowed outside without their faux space suits.

“My worst moment was probably being stuck in the airlock with a lot of poo …,” says volunteer Sam Payler, who was cleaning out the habitat at the time.

But somehow, they all got along and survived.

“The goal is to figure out how to pick a crew for these long-duration, isolated space missions,” says Martha Lenio of Waterloo, Ont., who led one of the eight-month missions.

“We’re the guinea pigs in a psychology experiment.”

Given that a trip to Mars and back could take up to two years, it’s crucial that NASA understands how that kind of journey might play on the minds of those who’d be in such close contact — and in potentially trying circumstances — for so long.

Data gathered by the Hawaiian project will be studied alongside observations from a separate experiment at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

In the Houston experiment, volunteers are cooped up for 45 days in an even smaller habitat — a mock spaceship — as if hurtling toward the stars.

There are no windows or even a chance to step outside.

That experiment is aimed at measuring the effects of monotony on the psyche of those doing effectively the same tasks, day after day after day.

“It’s basically looking at human nature, seeing how it may unfold,” says NASA behavioural health scientist Tom Williams.

He points to explorers through history who coped with similar monotony, citing those who long ago survived Antarctic winters, for example.

He adds, “We also know that not everyone can tolerate [monotony] at the same level. So it’s very important for us to understand what are those characteristics that allow someone to be successful at this.”

Perfecting Orion

Meanwhile, NASA is also pushing ahead on the biggest challenge of all — a spacecraft that can take people to Mars and back.

Inside a giant garage-like structure not far from a museum housing an old Saturn V rocket, NASA engineer Nujoud Merancy oversees work on the Orion space capsule.

At roughly the size of two minivans, it’s larger than the Apollo used for moon missions and is meant to one day help get humans to Mars.

She firmly believes it’s achievable.

“It’s my job, I build spaceships,” she says. “My job is to solve problems, [and] I think these are all things we can do.”

But she underlines the myriad unresolved challenges. One of which is simply anticipating and finding room for whatever would have to be brought along.

“All the food, water, oxygen, all the exercise equipment, everything people could need for two years in one spacecraft,” Merancy says.

Whoever goes will also need protection from radiation, ways to deal with illness, the capability to independently repair whatever breaks down en route — and, of course, a place to live once they touch down.

“And then you’re going to need a rocket to get them back off the surface of Mars,” she adds.

Will anyone really go?

Merancy agrees putting people on Mars is daunting, but believes it’ll happen within her lifetime.

“It’s not easy and we need a lot of people working on it to make it happen. But I certainly think it’s possible,” she says, adding that figuring everything out is “within the realm of human capability.”

There are also those who are less optimistic.

Among them is Toronto’s Randy Attwood, executive director of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, who is writing a book about the Lunar Module, the spiny-legged landing vehicle which 40 years ago set astronauts on the moon.

“I would love to see people go to Mars,” he says. But “I don’t think that’s going to happen.”

Attwood notes that engineers always seem to suggest such a mission is close at hand, but likewise seem to keep pushing back the yardsticks.

“After the first moon mission, Mars was 20 years away,” he says.

“And then after another decade, Mars was still 20 years away. And then after a few more decades, Mars was 30 years away.

“Mars is always so far in the future … just somewhere down the road.”

This, even as the upstarts at billionaire Elon Musk’s Space-X are making their own plans for a Mars trip, potentially within the next decade.

Working alongside NASA, the company has brought fresh excitement and determination to the idea of getting there. February saw the launch of a Falcon Heavy, the Space-X rocket designed with Mars in mind.

The rocket’s test payload, a Tesla electric car with the entertainment system playing David Bowie’s Space Oddity on an endless loop, is currently on its way to the red planet.

But sending a robotic rover, or a sports car, is a breeze compared with sending people.

Setting aside the issue of who foots the bill for the billions it would cost, even the most optimistic scenario indeed still puts a crewed mission to Mars many years in the future.

Still, as teams continue to chip away at that list of challenges, the idea of one day seeing footprints on Mars nudges ever closer.

As a people, “It’s how we progress,” says astronaut Saint-Jacques, of what he sees as an inevitable Mars mission. “Eventually it will become reasonable and natural to take a deep breath and dive in and make the trip.”

And the stars will look very different that day.