When Damien Maguire moved to the countryside outside Dublin, he struggled to keep the lights on at home because of the town’s constant power outages. He found a solution inside his electric cars: their batteries.

A tinkerer who posts videos of his hand-built vehicles on Youtube, Maguire devised a wiring system that lets him suck power out of them when they’re parked in the garage. Now that the house and cars are connected, he can also use the batteries to store energy from his backyard solar panels, another power source that’s not totally reliable given Ireland’s weather.

“You have the light-bulb moment,” said the 41-year-old electrical engineer. “There’s a big battery in the car, so how about I use that?”

An even bigger light-bulb moment is happening for utilities and automakers, who want to use the batteries inside electric cars as storage for the entire public power grid. The idea, known as “vehicle-to-grid,” is to someday have millions of drivers become mini electricity traders, charging up when rates are cheap and pumping energy back into the grid during peak hours or when the sun simply isn’t shining. If it works — and it’s a big if — renewable energy could get much cheaper and more widely used.

“We really, really need storage in order to make better use of wind and solar power, and electric cars could provide it,’’ said Daniel Brenden, an analyst who studies the electricity market at BMI Research in London. “The potential is so huge.’’

Today, fewer than one percent of the world’s vehicles are electric, but by 2040 more than half of all new cars will run on the same juice as televisions, computers and hair dryers, according to estimates by Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Once cars and everything else are fed from the same source, they can share the same plumbing.

Battery Boom

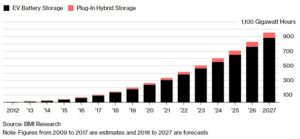

Global storage in electric and hybrid vehicles forecast to grow 9-fold over the next decade

Note: Figures from 2009 to 2017 are estimates and 2018 to 2027 are forecasts

As it stands, energy generated by wind and solar farms often goes to waste because there’s nowhere to store it. South Australia solved the problem by investing an estimated $80 million to $90 million to build the world’s biggest lithium ion battery on the edge of the Outback. The result is a massive cluster of white boxes that is essentially a huge reservoir for electricity. Inside are the same batteries Tesla Inc. uses in its cars.

But what if that reservoir was divided between millions of cars already on the road? That’s the vehicle-to-grid concept.

It’s promising because the newest electric vehicles can hold enough energy to power the average U.S. home for several days. For most drivers, whose cars sit idle 90 percent of the time, sharing their batteries would make good use of a very under-utilized resource. (It’s like Airbnb, but with car parts instead of seldom-used apartments.) For the utilities, borrowing people’s batteries would mean not having to build or buy them.

Sounds awesome.

In the real world, though, there’s a tangle of complications. Elaborate new computer networks would have to be built, carmakers and power companies would have to collaborate, and people would have to stop thinking of their cars as a private bubble. The main practical problem is getting drivers to charge up when there’s a power surplus, and getting them to give back when the public grid has a deficit, all the while making sure people’s cars never run out of juice.

To get a sense of the difficulties, consider the struggle the world’s No. 1 seller of electric cars, Nissan Motor Co., has had convincing customers in Japan to try a simple system like the one Maguire jerry-rigged for himself at his home in the Irish countryside.

By allowing car batteries to serve as a residential power source, Nissan says its vehicle-to-home service cuts utility bills by about $40 per month. Still, only about 7,000 car owners have adopted the system in the six years since it started, a tiny number compared with the 81,500 Leaf EVs that Nissan has sold so far in the country.

Declining to discuss any travails, a spokesman said the company is “very pleased” with its sales and sees growing consumer interest in the technology.

Meanwhile, Nissan is trying other experiments. Last year, it partnered with Japan’s biggest utility, Tokyo Electric Power Co., to design a vehicle-to-grid system that takes the Maguire idea and ratchets-up the complexity.

A small test this winter showed how hard it is just to get people to charge their cars at the right time. (Selling power back to the grid is a separate can of worms.) Nissan and the utility convinced 45 of their own employees to install home chargers and try monitoring electricity demand on weekends, using a smartphone app. Even though volunteers got free shopping points on Amazon as a reward for buying power when there was glut, only about 10 percent succeeded.

The big takeaway was that, since most people aren’t home in the early afternoon, the system won’t really work until there are fueling stations all around town at places like the mall or the park. The company is looking at lots of different ways to boost participation, according to Yukio Shinoda, a Tokyo Electric manager who helped organize the trial.

Jonn Axsen, an associate professor at Simon Fraser University in Canada, who has studied vehicle-to-grid systems, says it’s unclear whether power companies will be able pass-on enough cost savings to convince car owners to cooperate. “There is also a trust issue among some EV buyers, in terms of whether they trust their utility enough to manage the charging of their EV,” he said by email.

The first company to offer an actual product that allows drivers to both buy and sell power is San Diego-based Nuvve Corp., which has succeeded by focusing on business customers in Denmark, a double-whammy of smart targeting. Company cars have predictable routines that make it easier for Nuvve’s software to calculate how much electricity can be sold back to the grid without running out of fuel on the road. (And Danes are seriously into renewable energy.)

Since 2016, ten businesses with a total of 50 vehicles have bought the service, according to Nuvve, which teamed up on the project with Nissan and Italian utility Enel SpA. Tests are also underway at a handful of locations in Amsterdam, where Nuvve is collaborating with Mitsubishi Motors Corp. and Newmotion, a unit of Royal Dutch Shell Plc that operates charging stations throughout Europe.

It’s a slow beginning, but Nuvve Chief Executive Officer Gregory Poilasne says vehicle-to-grid systems could eventually speed up the adoption of electric vehicles once people realize their batteries can earn them money. Poilasne says his clients make more than $1,000 per car each year by trading power to the spot market.

For Maguire, the rural inventor, one thing that’s become clear is that car batteries can be a lot more useful than most people think. His latest challenge is seeing whether he can convert his diesel-guzzling BMW sedan into an electric car on a shoestring budget of less than 1,000 euro, or about $1,250.

“I joke that one day I’m going to finish up these projects and take up golf,’’ he said. “But the more I learn about these batteries, the more I try and the more I get out of them.’’