It could restore voices lost to neurological conditions.

People with neurological conditions who lose the ability to speak can still send the brain signals used for speech (such as the lips, jaw and larynx), and UCSF researchers might just use that knowledge to bring voices back. They’ve crafted a brain machine interface that can turn those brain signals into mostly recognizable speech. Instead of trying to read thoughts, the machine learning technology picks up on individual nerve commands and translates those to a virtual vocal tract that approximates the intended output.

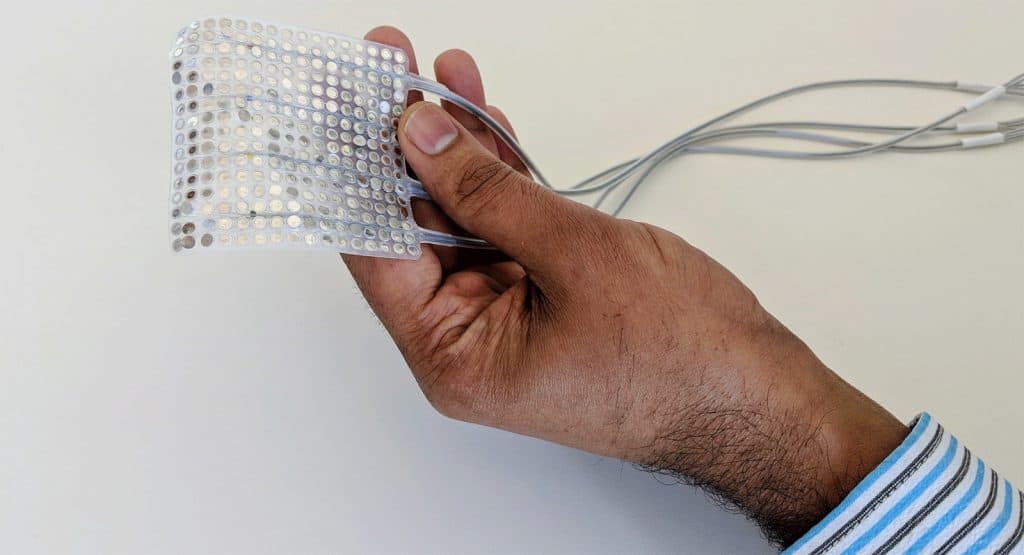

The results aren’t flawless. Although the system accurately captures the distinctive sound of someone’s voice and is frequently easy to understand, there are times when the synthesizer produces garbled words. It’s still miles better than earlier approaches that didn’t try to replicate the vocal tract, though. Scientists are also testing denser electrodes on the brain interface as well as more sophisticated machine learning, both of which could improve the overall accuracy. This would ideally work with any person, even if they can’t train the system before using it in practice.

That effort could take a while, and there’s no firm roadmap at this stage. The goal, at least, is clear: the researchers want to revive the voices of people with ALS, Parkinson’s and other conditions where speech loss is normally irreversible. If that happens, it could dramatically improve communication for those patients (who may have to use much slower methods today) and help them feel more connected to society.