Sorcerer Lodge can only be reached by helicopter and is in ideal spot for trees to grow

The owners of an alpine backcountry lodge near Golden, B.C., are trying to save the endangered whitebark pine trees that surround their remote mountaintop home.

The Sorcerer Lodge, which sits at an elevation of 2,050 metres in the Selkirk Mountains and can only be reached by helicopter, is in an ideal spot for the trees to grow. The whitebark pine favours high elevations with lots of sunlight.

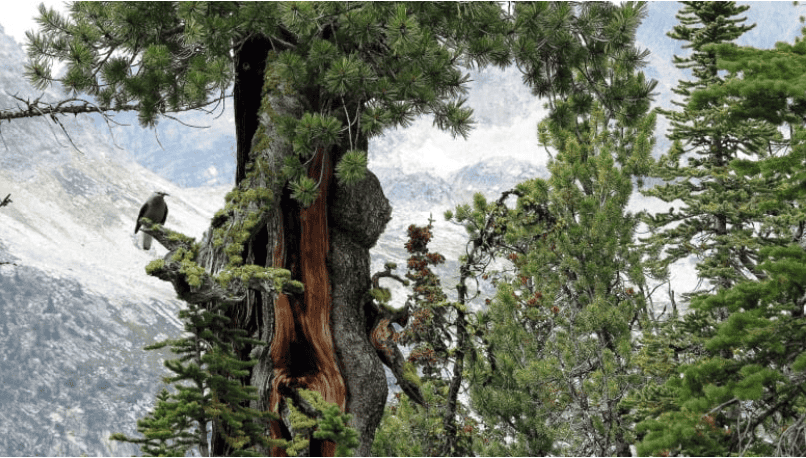

“Our trees … are some giant trees. They twist and turn in the branches and don’t grow like you’d expect most trees,” said Tannis Dakin, co-owner of the lodge.

“Every one is completely different. Some of the branches go straight out from the trunk and then dip back down to the ground and back up again. They’re quite the characters and they’re really beautiful.”

The trees are considered an important source of food for birds, grizzlies and other wildlife, and they also help hold the snowpack at higher elevations.

Dakin and the team at the lodge have been recognized by the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation for the work they’ve done to protect the trees.

The foundation has named the ski lodge as the first Whitebark Pine Friendly Ski Area in Canada. This means they are considered leaders in preserving these trees and in educating skiers who come to the area.

“In Canada I think they’re just trying desperately to get the word out about these trees and it helps to have people who live and work within them,” said Dakin.

The species of tree is considered so at risk that in 2018, Lake Louise Ski Resort in Banff National Park was fined $2.1 million by a provincial judge for cutting down 38 whitebark pine trees five years earlier.

The resort has since appealed the fine and requested it be reduced to $200,000, arguing the trees they cut down didn’t have a significant impact on the overall whitebark pine population in Canada. A decision in that case has yet to be made.

Protecting the trees

Dakin told Daybreak South host Chris Walker that she first got involved with protecting the trees 12 years ago, when she noticed they weren’t looking very healthy.

She began researching blister rust infection, a fungal infection that has killed a lot of whitebark pine trees, but there were inconsistencies with what she was seeing.

“I was struggling with trying to understand what I was seeing on the ground and what I was hearing and reading because it wasn’t matching,” she said.

Dakin was finding live trees among large patches of dead ones that were still producing cone crops.

Parks Canada and a team of researchers have been studying the trees to try to find out if some of them are resistant to blister rust. Dakin has been hosting PhD students at the lodge who have been coming to collect samples, and supporting researchers with volunteer labour, helicopter costs and accommodation.

“The research is adding little bits and pieces of the puzzle and I think there might be some hope,” she said.

They are now planting seedlings that appear to be resistant to the infection in an attempt to spread some genetic diversity and increase the population of whitebark pines.

“I’m hopeful and I think we have to try. There’s really no alternative.”