Three chemotherapy cancer drugs face national shortages, putting pressure on health care providers

Cancer specialists are concerned national shortages of three vital cancer drugs could lead to a time when they could run out of treatment options for patients in Canada.

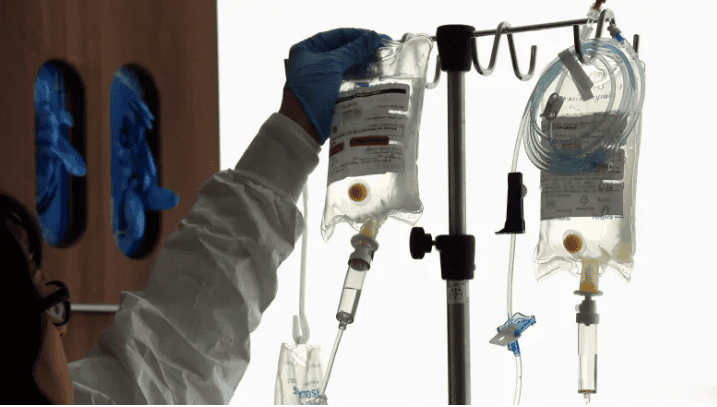

The three drugs are all injected into patients’ veins.

The federal government’s drug shortage reporting website lists all three as experiencing national shortages, meaning the scarcity problem could affect patients throughout the country.

At hospitals in Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, oncologists, pharmacists and nurses have all scrambled to find alternatives, make substitutions and share precious vials.

“My point in raising this publicly is not to alarm patients,” Dr. Gerald Batist, director of the Segal Cancer Centre at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital.

“But to start to bring this into the public discourse so that we have some pressure on our government and on drug producers to find a solution to this.

“It’s not really clear that any efforts are being made to solve this problem in a more permanent way.”

The drugs include vinorelbine, which treats non-small cell lung cancer and metastatic breast cancer. Leucovorin is often used in combination with chemotherapy drugs to decrease their toxic effects. Etoposide treats lung cancer and testicular cancer. It can also accompany bone marrow transplants.

In an email to CBC News, Health Canada said it “recognizes the impact that these shortages have on the patients who rely on these important medications and is taking action to address them.”

Dr. Bruce Colwell, a medical oncologist at QEII Health Sciences in Halifax, sees more frequent drug shortages at his hospital.

“I’ve dealt with sometimes two, three [shortages] but eight is for me a record,” said Colwell, who’s also president of the Canadian Association of Medical Oncologists.

He hasn’t reached the frightening point of telling a patient that treatment has been stopped because of a shortage.

Short notice concerns

The problem is that hospitals often hear about shortages with as little as one day’s notice. Staff scramble to find alternative drugs that work equally well but may have a shorter track record.

Geoff Eaton, 43, said patients need to be the central focus of suppliers, pharmaceutical companies and governments. He was first diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia at age 22.

“I didn’t have months or years to wait,” he said. “I had a very small window that I had to access this treatment.”

When the St. John’s resident needed etoposide during a relapse in 2001, he was told a nursing shortage in Toronto would mean an extra round of chemotherapy. He pushed for — and received — a bone marrow transplant in Ottawa instead.

“It’s a very tough situation,” said Eaton, executive director of Young Adult Cancer Canada, a group that organizes support for young cancer patients.

“You are kind of faced with this unexpected additional burden and challenge amidst probably the most challenging situation of your life.”

Earlier this year, Health Canada said it facilitated import of an international supply of etoposide as a short-term measure until the anticipated shortage end date of Sept. 30.

Sandoz Canada, one of the companies reporting a shortage of etoposide, said the supply “has been disrupted due to a manufacturing set-up change to maintain our product’s highest quality standards. For now, the reintroduction is planned for the second quarter of 2020.”

Vinorelbine shortages were reported by Fresenius Kabi Canada Ltd, Teva Canada Ltd. and Generic Medical Partners Inc. (GMP).

“GMP has reported that it is implementing a distribution strategy in order to supply product at 75 per cent of the demand for orders received and it is seeking to increase production to meet national demand by October 2019,” Health Canada said. The federal department said it continues to monitor the supply closely.

Discontinuation and disruptions

Pfizer said it discontinued vinorelbine “after a careful evaluation of the availability of other treatment options in Canada.”

It’s unknown when Teva and Pfizer Canada’s leucovorin shortage will be resolved. Health Canada said it’s working with companies “to explore the possibility of accessing international supply as soon as possible.”

But Batist is losing patience.

“They talk about problems with shipping, which is a little bit unusual for 2019,” he said. “We’re having a great deal of difficulty finding credible excuses.”

The three drugs are no longer patented and there’s little incentive for manufacturers to keep up inventories, Batist said.

He suggested legislation might be needed to force drug makers to make products available if they want to sell medicines.