Fake honey cut with corn syrup, rice, beet and other sugars is still pouring into Canada and onto grocery store shelves.

The producers, who pride themselves on turning out the real thing, have been abuzz about the food fraud for years. They say they are feeling the sting and consumers should be aware.

Since June 2018, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has been zeroing in on fake honey, using “targeted surveillance.”

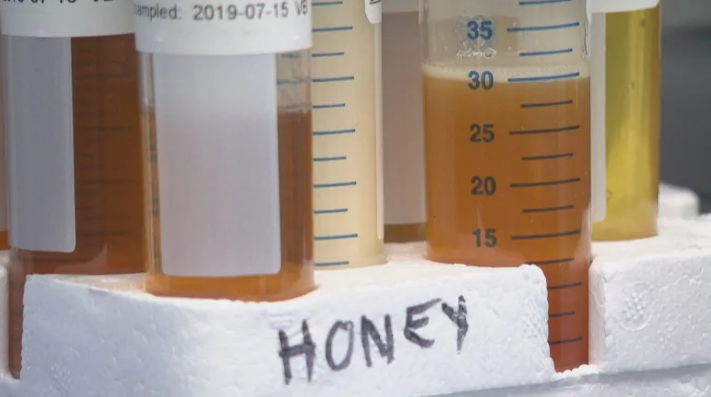

The federal agency collected 240 samples across Canada from honey importers, brokers, distributors, blenders, processing facilities and grocery aisles.

While all the domestic samples proved to be authentic, more than a fifth of imported honey from a number of countries — including Greece, China, India, Pakistan and Vietnam — failed tests at the CFIA lab in Ottawa.

“Twenty-two per cent [of the samples] were found to contain foreign sugars such as corn syrup, rice syrup and cane sugar syrup,” Jodi White, a national manager in CFIA’s consumer protection and market fairness division.

The CFIA has been testing for adulterated honey for more than two decades, but this year’s inspection targeted some suppliers that had been flagged in other jurisdictions for issues such as unusual trading patterns.

“It’s based on targeted sampling,” White said. “It’s not necessarily indicative of the overall market.”

The inspection has stopped 12,800 kilograms of adulterated honey, valued at around $77,000, from entering the Canadian market.

Beekeepers can’t compete

Chris Hiemstra, a third-generation beekeeper, is among honey producers who say they’re feeling the sting from cheaper, adulterated imports.

He knew he had to expand the family business if he wanted to keep his honey farm in Aylmer, Ont.

“We’re trying to support the family and selling honey wholesale by the barrel on the world market was really difficult and unsustainable,” he said. “It was for survival.”

Hiemstra has spent 20 years building his farm, Clovermead, into a larger, agri-tourism adventure farm where locals and visitors pay to tour the property. Patrons take wagon rides, visit farm animals and learn about, taste and buy honey produced by the farm’s 24 million bees.

The business is doing well thanks to the tourism, as well as revenue from honey sales online, but Hiemstra worries about fellow honey wholesalers across Canada trying to make ends meet.

“They’re big producers and they need a fair price for their honey. Otherwise, they cannot pay their employees and support their families. Those are the people that are impacted.

“Someone can sell sugar for 20 cents a pound and say it’s honey against someone that needs $2 a pound to make a living. That [price] gap is huge and there’s no way you can compete against that.”

Looking for real honey? Look local (and for bee stings)

Honey tends to change hands a lot on its way to store shelves, and it can be hard to know at what point the product gets diluted.

“It is a very complex supply chain, and this is something we’re looking at,” White said, speaking inside the CFIA lab.

“[We’re looking at] where the vulnerabilities are in the supply chain and where is adulteration or other misrepresentation being introduced.”

Hiemstra said you can be sure it’s not the beekeeper.

“At the beginning, the beekeeper works with bees, spinning the honey out of the frames, putting it into either jars or into a barrel,” he said in Clovermead’s honey shop.

“Someone after that is taking it and putting it in big vats, and blending it and mixing it. That’s not the beekeeper; it’s something further down the line,” he said, suggesting some unprofessional “professional” food handlers may be to blame.

Hiemstra has some advice for consumers who want to be sure they’re getting the real stuff.

First, “when it’s really cheap, you’re probably getting what you’re paying for,” he said.

“I would say they should try to find somebody that’s got their name on a bottle.”

As for vetting beekeepers?

“Look at them. See if they’ve got dirt on their hands and they’ve got swollen cheeks from bee stings.”