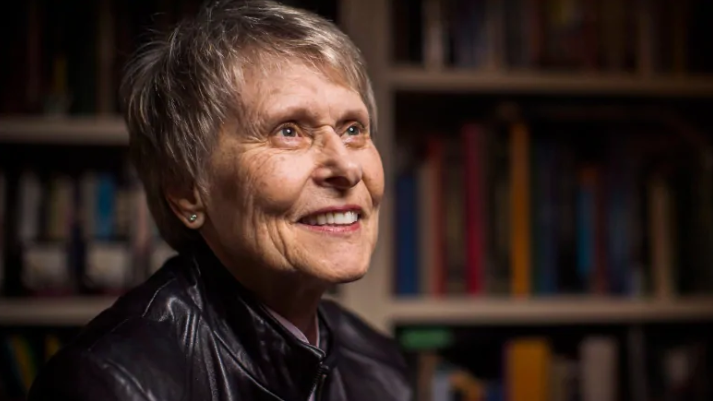

Space science is strengthened by diversity of gender, ethnicity and academic backgrounds, says Bondar.

When she was a young girl growing up in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., Roberta Bondar knew she wanted to go into space.

She built and played with plastic model rockets and space stations. Her aunt, who worked at Florida’s Cape Canaveral, would send her posters and crests from the space program.

And in 1969, when the Apollo 11 mission put man on the moon, Bondar saw it as an affirmation of that dream.

At the time, though, the images of astronaut crews on the evening news featured only men.

Still, that never dulled her resolve.

“I had to say to myself, ‘You may not be a boy, but you’re going to go and get some things so that people can’t ignore you.’ So I got four degrees,” Bondar told The Current.

“I certainly was the most educated person — academically — that has gone into space for Canada … because I did not want people to ignore me as a woman.”

Having earned those four degrees, including a PhD and an MD, Bondar took part in the STS-42 research mission in 1992, aboard the space shuttle Discovery. She became the first Canadian woman, as well as the first neurologist, to go to space.

Statistically, Bondar is still a rarity. Out of the hundreds of astronauts to embark on missions outside Earth’s atmosphere, only 59 have been women, according to NASA.

‘You’re out of line’

Bondar left the Canadian Space Agency in September 1992, but continued her research in space medicine with NASA.

She also pursued a career in photography, and served as chancellor of Trent University from 2003 to 2009.

Bondar did not elaborate on why she said she wasn’t “allowed” to continue her career in space, but told The Current she suspected some men she worked with were intimidated by her accomplishments and capabilities.

She recalled one encounter with a male astronaut who told her she spoke to her colleagues — all men — “in a very condescending manner.”

“I looked at this man and I just remembered the movie The Right Stuff, when there was a scene where one of the other astronauts said, ‘You’re out of line.’

“I just said, ‘You’re out of line, and you need to look at your own behaviours. And I’m not changing, because I’m contributing as a team member.'”

Bondar said these moments in her career were difficult and that she believes she wouldn’t be immune to such conversations even today.

‘Hyper-masculine’ origin

The potentially hostile environment for women in the aerospace industry — and NASA in particular — may be traced to its military roots, says space flight historian Amy Shira Teitel.

“NASA’s a civilian organization. But the people that ran it, most of them had military backgrounds and that, at the time, was an all-male, like, hyper-masculine arena,” she said.

“I think, you know, when you get these guys in their 50s and 60s running the agency, or you get these hotshot test pilots who are used to being top dog, top of the pyramid, some of that machismo kind of bleeds into anything else that you do.”

According to Teitel, astronauts were originally chosen from the ranks of military test pilots, who, at the time, were overwhelmingly men and “treated like rockstars.”

It wasn’t until 1978 that NASA accepted mission specialists, such as scientists, as astronauts. That was the first class of astronauts to include women, African-Americans and Asian-Americans in their ranks.

Bondar also said some of the criteria needed to select astronauts may end up “deselecting” people, including women, who may actually have everything needed to do the job.

“They don’t need to have to do a four-minute mile. They don’t need to show that they can beat somebody else in a run down the road, or a swim in the pool [to prove] they’re better than somebody else to do that particular job,” she said.

“I think we have to look at how we envision our society, and how it is best going to be represented. And we just have to make sure that we don’t try to deselect people on criteria that are really irrelevant.”

Diversity strengthens science

Bondar believes that the future of spaceflight and space science needs more diversity, whether in gender, nationality, ethnicity or academic background.

That said, she isn’t a fan of a proposal put forward by National Geographic to gather an all-female crew for a future mission to Mars.

The article, which was part of a special commemorative issue about the Apollo mission and the future of space travel, posited that because women on average weigh less than men, they would need less fuel to be transported. Plus, an all-women crew (with male sperm samples safely tucked in the cargo hold) would be well-suited to off-world population efforts.

Bondar doesn’t see it that way.

“We have to believe that we can do the best we can. We can’t do that just with one segment of our population, with one gender. We just can’t.”

NASA recently pledged to put a man and a woman onto the moon by 2024, as part of its Artemis program, with the hopes of building a permanent human presence on Earth’s lone satellite.

Bondar believes, however, that Canada has an advantage precisely because of its diversity.

“I think we’re just going to see Canada become a stronger and stronger contributor to all fields of science, especially if we have the inclusion of a lot of women, if we have inclusion of a lot of men and a lot of people who come from different cultural backgrounds, who can give us a different way of viewing a problem,” she said.

“Because that’s what science is all about: it’s a way of thinking and approaching a problem and trying to find a solution.”