Much-hailed agreement left openings for steel and aluminum tariffs to snap back

“Don’t bask in the glory of this one,” United Steelworkers president Leo Gerard told CBC’s The House podcast last week, casting a skeptical eye on the agreement to end steel and aluminum tariffs.

The deal points to where the Trump administration’s protectionism may be headed next — and it’s not really a return to a North American free trade zone for steel and aluminum products.

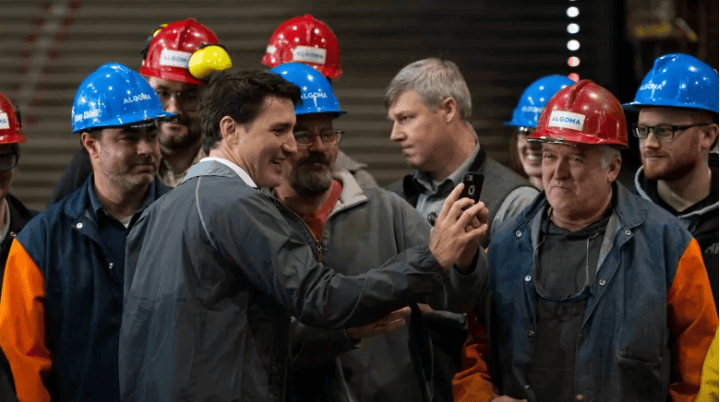

That didn’t stop Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland from touring Canada, striking celebratory poses with the grateful hard-hats-and-overalls crowd last week. Trudeau talked to aluminum workers in Sept-Iles, Que. and steelworkers in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont. Freeland met steelworkers in Regina before heading to meet more aluminum workers in Jonquiere, Que.

Their message at every stop: we had your backs. Patience and firm persistence paid off. Sault Ste. Marie MP Terry Sheenan even introduced Trudeau as their “man of steel.”

“Canada is able to make sure that we’re taking care of our people,” the prime minister said, sporting an Algoma Steel jacket. But, he acknowledged, there’s still more work to do.

If everyone at those events was being completely honest, they’d admit things aren’t returning to how they used to be. Workers must steel themselves for this: the U.S. hasn’t abandoned protectionism. Rather, it adjusted it when it became politically expedient to do so.

The White House needed allies in its escalating trade fight with China. This tariff deal cleared the way for a much-needed trade win on the relatively simpler North American front.

But a “full lift” of the tariffs didn’t really come without concessions, despite what Trudeau suggested May 17.

“There wasn’t a way to this without some sort of concession to the United States,” said former U.S. diplomat Sarah Goldfeder as the deal was announced. “This is a necessary evil.”

Here are a few still-unanswered questions about where things stand now:

What’s a ‘meaningful surge’?

The agreement is what trade watchers call a “snap back” deal. Yes, the tariffs were removed. But the U.S. reserved the right to slap them back on — specifically, “in the event that imports of aluminum or steel products surge meaningfully beyond historic volumes of trade over a period of time.”

Freeland has been asked to define a “surge” and couldn’t. There’s a conversation still underway with the U.S. to flesh out how this language should be interpreted.

Canada’s hope was that this part of the agreement would never be used.

Catherine Cobden of the Canadian Steel Producers Association told CBC News this week she doesn’t have a clear definition for “surge” either, but she’s hoping for a way to engage with the Americans and nail it down.

Otherwise, what’s to stop the Americans from torquing any increase in Canadian imports into a industry-threatening “surge”? What time periods would be compared? How would these volumes be calculated?

Sometimes, data can be manipulated to show whatever you want the numbers to show. And if tariffs are re-applied, Canada could no longer retaliate with tariffs on politically sensitive commodities like orange juice or bourbon.

Are there really no quotas?

Both the Mexicans and the Canadians said they wouldn’t settle for a deal that fixed quotas on their exports. But, as Carleton University’s Meredith Lilly observed on Power & Politics last week, “there’s language in the agreement that suggests perhaps we have quota by another name.”

The agreement lays out how the U.S. “may” request consultations before imposing duties at the same rate as the previous tariffs, “with consideration of market share.” In other words, Americans don’t want Canada’s market share to grow.

Is this a quota in disguise?

The U.S.–Mexico agreement is less subtle, saying that in assessing whether there has been a surge, Washington will consider that the U.S. may require “225,000 tonnes of billet from Mexico” and new investment in Mexico may require “200,000 tonnes of cold-rolled steel.” Those are negotiated quotas, hiding in plain sight.

What kind of Canadian steel is still a target?

The new (but undefined — officials are working on it, Freeland’s spokesperson says) monitoring regime for Canadian and Mexican imports “may treat products made with steel that is melted and poured in North America separately from products that are not.”

Freeland’s office emphasizes that the wording here is “may,” not “will.”

Only a handful of facilities in Hamilton and Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., make steel from iron ore in integrated mills. Most of Canada’s producers are smaller facilities for electric-arc steelmaking, often from scrap.

Where does that scrap come from? Even if it’s not from offshore — industry representatives say that’s rarely profitable — can they prove the integrity of their supply chains?

If they lack the right paperwork, Canadian steel products could be stalled, or even rejected, at the U.S. border, as eagle eyes track any traces of Chinese steel. It creates uncertainty for exporters — a classic non-tariff barrier to trade.

“There’s a presumption that [Americans] would use any opportunity to restrict market access,” trade consultant Dan Ciuriak said. “Is this something we extracted from them at great pain, that they would claw back at the slightest excuse?”

Are more safeguards coming?

The United Steelworkers union, and Cobden’s CSPA, still want Canada to put up more tariff barriers to protect its market. Spokespeople like Gerard warn about “countries that cheat because they want dollars”; because the world still makes more steel than it needs, they fear foreign steel displaced from the U.S. could somehow flood into Canada.

But Canada’s safeguard process has already run its legal course. The Canadian International Trade Tribunal concluded surtaxes were only justified on two offshore products — heavy plate and stainless steel wire — for the next three years.

There’s a difference between unfairly dumped steel — which Canada investigates regularly, implementing dozens of different duties — and fairly priced foreign steel, which meets legitimate needs that domestic producers cannot or will not serve. Manufacturers and construction companies that import steel were relieved when the government followed the tribunal’s advice and the provisional surtaxes imposed on five other steel products ended last month.

A working group has until early June to consider other ways of supporting Canada’s industry.

Will this help the new NAFTA pass?

After saying initially that the end of the tariffs meant things were “full steam ahead” for ratifying the revised North American trade agreement, Freeland and Trudeau were using more cautious language last week.

Freeland would make no predictions about ratification timing during a CBC Radio interview Tuesday. Trudeau has talked about ratifying in co-ordination with Washington.

Democrats in the U.S. Congress have suggested several parts of the deal must change before they’d proceed with a vote, including strengthening intellectual property provisions for biologic drugs, a move that could increase pharmaceutical costs.

Vice-President Mike Pence is scheduled to visit Ottawa next Thursday to promote ratification of the revised NAFTA deal. The Trudeau government may long to conclude this saga as well.

But it’s risky to draft and pass an implementation bill to change Canadian laws based on an agreement that’s still fluid in Washington. What if they made Canadian drugs more expensive than they actually needed to be to get a deal? How would that play in an election campaign?

No mention of NAFTA legislation appeared on the House of Commons notice paper in time for a bill to be introduced on Monday, when the House returns for what is scheduled to be its final two- to four-week stretch before the summer.