Imperfect testing among the problems businesses face with cannabis in the workplace

Seven months after the legalization of recreational cannabis, Garnet Amundson’s worries have not abated.

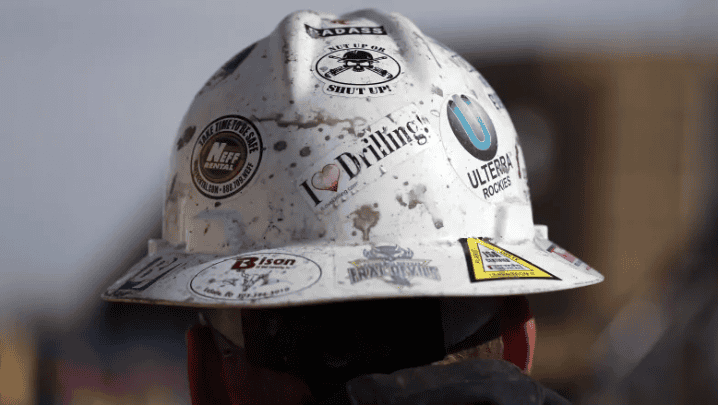

Amundson is chief executive of Calgary-based Essential Energy Services, with nearly 400 workers, including 350 in safety-sensitive roles in the oilpatch.

Topping his list of concerns is having employees who can pass any type of drug test on any given day and arrive at work without any impairment.

Not only does his company drug test employees in certain instances, but the staff may also be tested when they perform work at a facility owned by a different firm. In that case, Amundson said his workers have to meet the standards of the other company.

“Employees have to be completely clean at all times, so they can access these top customers and get on to their job sites,” he said.

It’s a situation underscoring the human resource and legal issues created by the legalization of cannabis for industries where any sign of impairment is closely monitored and safety is a priority.

The oilpatch, for example, has worked hard to get a handle on substance abuse for several years and the legalization of recreational cannabis presents another challenge for companies dealing with the often thorny issue of drug testing.

Testing for cannabis is not as advanced as using a breathalyzer to gauge someone’s impairment from alcohol. A urine test for cannabis, for instance, can detect THC, but can’t necessarily judge a person’s level of impairment.

“I think people maybe have been a bit misinformed believing that there is a completely accurate and reliable way to test for impairment with cannabis,” said Amundson.

No wonder the legalization of cannabis is proving to be a logistically challenging for Amundson and other employers across the country.

Legal grey areas and a lack of definitive tests mean “complete abstinence from some of these substances is required,” Amundson said.

Impairment is a concern in many industries such as oil and gas, forestry, mining and transportation, where workers are at a high risk of injury.

Other companies in different sectors also continue to grapple with the legalization of cannabis and, in particular, how to respect a worker’s right to consume the substance while also ensuring no one is impaired on the job.

“It’s a challenge for all employers in Canada, but especially small and medium-sized businesses that don’t have the financial or technical resources to manage this themselves,” said Tim Salter with the Drug and Alcohol Testing Association of Canada.

The major active ingredient in cannabis, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), can be found during urine testing up to 30 days after a worker uses cannabis, said Salter, but that only provides so much information.

“There’s really no way for employers to reasonably screen for impairment,” he said, “outside of doing a blood test which is not going to happen at the workplace.”

That’s where legal issues can occur. If there is an accident on a job site, a company is allowed to do post-incident drug testing. The urine sample may find traces of THC, but again, the test can’t judge the level of impairment. That’s why a company may not be able to say whether the worker was at fault because of cannabis or not, since there is no definitive proof that THC contributed to the accident.

“Employers are just forced into this corner of promoting abstinence,” said Salter. “It’s most definitely a mess because the governments really haven’t done a great job of preparing the industry for the legalization of cannabis.”

Eventually, Salter said the court system will have to decide on many of the issues cannabis presents for employers.

One workplace dispute was in front of the Newfoundland Supreme Court recently focusing on a construction labourer who was working on the Lower Churchill hydroelectric project in Labrador.

The man was prescribed cannabis to manage pain due to Crohn’s disease and osteoarthritis, since other medication wasn’t as effective. His company tried to accommodate his use of cannabis, but couldn’t.

Ultimately, the construction company wouldn’t give the man any work because of the risk of impairment in the safety-sensitive job site. The province’s top court agreed, pointing to how accommodating the worker “would amount to undue hardship” for the company.

Each case is different, but the court ruling shows how companies could refuse work to those who use cannabis, medically or not, depending on the dose and the type of job.

Safety first

So far, the legalization of cannabis has not contributed to an increase in workplace accidents, according to Murray Elliott, the chief executive of Energy Safety Canada, although it’s too early for reliable statistics.

“There has been very little impact or change in impairment in the workplace,” said Elliott.

While testing techniques for cannabis are evolving, Elliott said the accuracy is good and there are general guidelines companies can follow to gauge what level of THC in someone’s body is a significant risk of impairment.

“There is not necessarily a direct link between the levels of cannabis that show up in testing and whether there is impairment or not. It’s really only a risk of impairment,” he said.

In preparing for legalization, companies took a range of approaches, such as updating their existing drug and alcohol policies.

Sinopec Canada, an oil and gas producer, spent nine months before legalization to create a policy that would respect the rights of workers, legally protect the company, and also ensure a safe workplace.

Kara Bennik, a human resources advisor with the company, said they set out to be as informed as they could about the issue, consulting different departments to incorporate a range of views.

“We’re still evolving and growing our program,” said Bennik. “The reality is that future legislation is going to continue to come in.”

Considering the struggles of the oilpatch in recent years, the sector hasn’t hired too many workers, but when that happens, Amundson, with Essential Energy Services, worries there will be fewer qualified applicants than before because of the pre-employment drug test.

Already during some hiring, Amundson said the applicants are asked at the end of their interviews if they would pass a drug test.

“They look at us and say most of the time, ‘what do you mean?’ I don’t think a lot of the time we get an unequivocal ‘Absolutely!'”

Often, he said they ask if they can come back in a few weeks.