‘Something needs to be done,’ says commanding officer about stability issue that’s kept ships from patrolling

Canada’s $227-million fleet of mid-shore coast guard vessels are rolling “like crazy” at sea, making crews seasick and keeping some ships in port during weather conditions where they should be able to operate, CBC News has learned.

Canadian Coast Guard records and correspondence obtained under federal access to information legislation raise questions about the patrol vessels’ seagoing capability and reveal a two-year debate — still unresolved — on how to address the problem.

At issue is the lack of stabilizer fins — blades that stick out from the hull to counteract the rolling motion of waves — on nine Hero class ships that were built by the Irving Shipyard in Halifax between 2010 and 2014.

The problem is reportedly so bad that a trip along the West Coast required one Fisheries and Oceans Canada supervisor in B.C. to place rolled up jackets under the outer edge of his bunk to keep him pinned against the wall instead of being tossed out by the amount of roll in the ship.

“It goes without saying that the crew [is] in favour of [stabilizers],” wrote supervisor Mike Crottey. “Seasickness is felt both by conservation and protection and coast guard personnel and has an impact on vessel operation.”

Retrofit debated since 2017

The coast guard decided it did not need stabilizers when the ships were being built, but has been considering retrofitting them since 2017 amid criticism from commanding officers and others who serve on board.

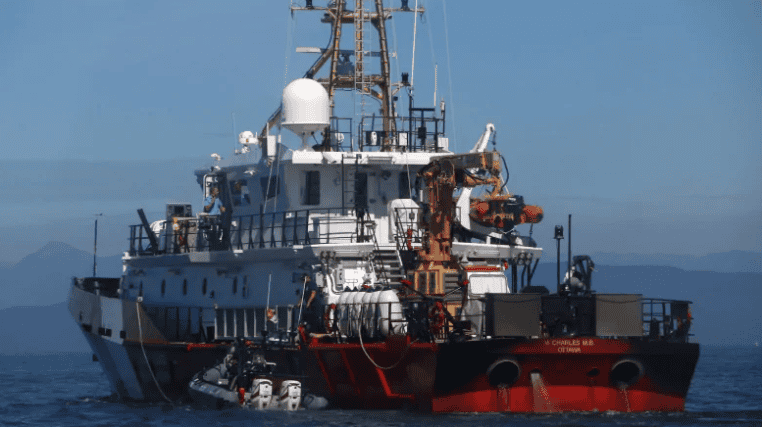

Crottey said that in exposed water, the skipper of the CCGS M. Charles sets a weather course to “keep the ship from really rocking around,” which can result in more fuel consumption and increased operating costs.

“This course is based on the swell and the wind direction and is used [to] alleviate excessive ship motion and not based on the shortest distance to destination,” Crottey wrote.

The vessels, which are 42 metres long and seven metres wide, are known as the Hero class since each is named after an exemplary military, RCMP, Canadian Coast Guard or DFO officer. Their primary mission is fisheries enforcement and maritime security in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, the Great Lakes and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The ships also provide search and rescue and pollution control.

The coast guard denies there is any problem with the safety and stability of the fleet. However, in a March 2017 “configuration change request” to have stabilizers installed, coast guard project manager David Wyse described “an increased hazard of crew injuries and program failures.

“All vessel operators agree the Hero class vessels require stabilizers in all area of operation,” Wyse wrote. “Program operations can suffer [due] to the fact that the vessels have extreme roll in high sea state conditions.”

More than a year later, in May 2018, Wyse relayed an unidentified at-sea testimonial: “I’m rolling 15 degrees port and starboard (30 degrees total) out here today and the winds are less than 10 knots and seas are less than one metre. We need to make this platform more workable.”

‘This ship rocks like crazy’

Those concerns were echoed by Sgt. Hector Chaisson of the RCMP Marine Security Enforcement Teams who, in September 2017, wrote “greater stability of the ship would be appreciated by the entire crew and would avoid repeated seasickness.”

Fred Emeneau, commanding officer of the CCGS G. Peddle, was more blunt in his assessment.

“All I know is something needs to be done,” he said. “They want us to patrol through the nights whenever possible. The crews are getting fatigued trying to achieve this in North Atlantic conditions in the winter. Most 45-foot [13.7-metre] fishing boats we work around are wider than the [mid-shore patrol vessels].”

In the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Francois Lamoutee, commander of the CCGS Caporal Kaeble emailed on August 2018 with his opinion.

“By the way stabilizers should never have been removed from the original design. Please put them back ASAP. Losing a few cubic metres of fuel space will be a minor factor compared to the huge gain in stability, safety and comfort for the crew.”

The issue of excessive rolling isn’t limited to expeditions at sea.

Steve Arniel, commanding officer of the CCGS Constable Carrière on the Great Lakes, emailed in June 2018, saying, “This ship rocks like crazy tied to the dock!”

Dozens of missed days at sea

Another concern is the time the vessels spend holding up the wharf because of weather.

In the 2016-17 season, the Nova Scotia-based CCGS Corporal McLaren lost 44 per cent of ship time allotted to fisheries patrols — 112 of 252 days — because the vessel could not sail due to weather, according to its commanding officer.

Greg Naugle reported that “87 days of those weather days were in seas less than three metres, which is inside the TSOR [technical statement of operational requirements] operational envelope.” The year before, 107 days were lost when seas were under three metres, he said.

The coast guard sent CBC News records of weather delays for the 2017-18 season for the two mid-shore patrol vessels based in the Atlantic.

It said the CCGS G. Peddle had 96 weather delay days out of a planned 302 operational days, while the Corporal McLaren had 97 weather delay days out of 309 planned operational days. It did not say how many weather delay days involved seas under three metres.

A satellite tracking comparison of fishing activity versus patrol coverage in southwestern Nova Scotia was redacted on the grounds disclosure jeopardized security.

But Michael Grace, a DFO Maritimes offshore surveillance supervisor, wrote in that report there are “several examples” of a mid-shore patrol vessel staying in port due to weather “while significant on-water activity is taking place offshore.”

Ottawa looking into issue

None of this is a surprise to Jeff Irwin, a recently retired 33-year federal Fisheries officer who heard complaints as a member of the national executive of the Union of Health and Environment Workers. The union represents DFO conservation and protection officers.

“They can’t go out to sea and do the fisheries patrols when the fishermen are on the fishing grounds because they can’t handle the wave action, they can’t handle the sea. So as a result they lose a lot of patrol time,” he told CBC News in an interview.

Documents released to CBC News blank out cost estimates on retrofitting the vessels with stabilizers.

Federal Fisheries Minister Jonathan Wilkinson told CBC News the government is “definitely looking into” the issue. “It’s obviously not great if we’re losing sea time,” he said.

An analysis of options prepared for the coast guard by a Dartmouth, N.S., naval architecture firm said stabilizers were intended as original equipment.

“Due to many changes to the original design the vessel had become too heavy and it was decided to drop the stabilizers to save weight and reduce hull resistance,” said an assessment by Lengkeek Vessel Engineering prepared for the coast guard.

Stabilizers would add weight

Mario Pelletier, deputy coast guard commissioner, disputes that, and said stabilizers were never dropped because the coast guard never asked for them.

He said they are now being considered as part of planning for a mid-life modernization. In the meantime, the coast guard is grappling with the added weight and space that would be required to put them on.

“We’re going to do the feasibility study and I think it looks promising but there will be trade-offs that fleet will have to agree to (carry less fuel, vessels that go slower because of the appendages) so I don’t know that you’d be in a position to promise stabilizers,” wrote DFO naval architect Tracey Clarke in a May 2017 email to David Wyse.

Nearly two years later, the coast guard and its managers have not made the decision.

Irving Shipyard did not respond to a request for comment on the issue of installing coast guard stabilizers.

CBC News reported three years ago that the mid-shore patrol vessels have been the subject of numerous warranty claims by the coast guard, including some for faulty wiring, polluted water tanks, premature corrosion and a gearbox failure.

At the time, Irving Shipbuilding said the ships were built and inspected according to international and Transport Canada safety requirements, warranty issues were being addressed and the ships performed extremely well.

‘No stability issues on those ships’

Pelletier told CBC News the vessels meet the operational standard set by the coast guard. The ships can operate in seas of more than three metres, but certain activities — including launching rigid hull inflatable boats and hauling lobster or crab pots — may not be safe in severe seas, he said.

As for the wave riding of mid-shore vessels, Pelletier said that’s a question of comfort, not stability. Occupational health and safety records show nothing out of the ordinary in terms of seasickness on the ships, he said.

“The quicker a ship rolls and comes right up, the better stability it has, it’s less comfortable. That’s the difference,” he said.

“If a ship rolls slowly and doesn’t come right up properly — that’s a huge stability concern. To be clear, there are no stability issues on those ships.”