Unclear what proposals would cost, or if there would be support from management, public

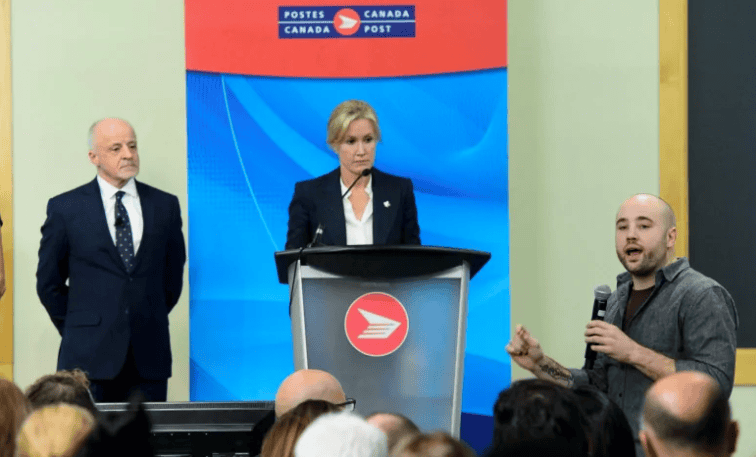

As arbitration grinds on at Canada Post following back-to-work legislation passed in November, the union has made a series of proposals beyond standard contract negotiations on wages and benefits: they want the Crown corporation to open a new bank for low-income people and turn the post office into a hub for green technology

With one of the country’s largest vehicle fleets that could be converted from gas to electric power, 6,000 distribution outlets where electric car-charging stations for consumers could be built, and old buildings ready to be retrofitted with solar panels, the post office is well positioned to help Canada transition to a greener economy, said the union’s president.

There’s one major problem with the ambitious proposal, according to critics: Who’s going to pay for it?

Debates over how institutions should reduce their carbon footprint — and how the changes should be financed — are playing out across the public and private sectors as leading scientists warn the world has just 12 years to drastically reduce emissions to avoid catastrophic climate change.

“Climate change is the biggest challenge facing humanity,” Mike Palecek, president of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW) said in an interview. “We have to address it … Canada Post is the biggest piece of federal infrastructure, it has the largest vehicle fleet in the country, it would be a good place to start.”

He couldn’t say how much the proposals would cost.

Canada Post declined to comment on demands for a postal bank and the green retrofit. “With the arbitration process now underway, it would be inappropriate to comment on specific negotiations issues,” a spokesperson told CBC News by email. “We are committed to the process and are fully engaged with the union and the arbitrator.”

A government-appointed arbitrator is expected to announce a deal for a new contract in March, after workers on rotating strikes were legislated back to work in late November amid long delays for packages amid the Christmas delivery rush.

Banking on change

The proposed postal bank is aimed at rural residents, including First Nations, who often don’t have easy access to a bank branch, said John Anderson, researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, a think-tank whose advocacy areas include reducing income inequality. It would also benefit low-income Canadians, including pensioners and the working poor who often depend on payday lenders for loans, cheque cashing and other financial services.

Popular in France, the U.K., Italy and other countries, postal banking in Canada would almost certainly be profitable, he said, citing a 2016 survey that suggested three million Canadians and about one-third of businesses would use financial services from the post office.

The post office already handles financial transactions, and the federal government runs other successful banking organizations, such as the Export Bank of Canada and Farm Credit Canada, Anderson added.

Canada’s federal pension plan even invested in China’s postal bank, he said, indicating that such plans are financially viable.

“The federal government — through its ownership of Canada Post — is the only body that could bring modern financial services to every community in Canada,” Anderson said. “That would be great competition for the big banks, which are profitable partially because of the high service fees they charge compared to other banks worldwide.”

Taxpayer interests

Canada Post hasn’t been receptive to demands for the green retrofit or the postal bank, according to CUPW’s president.

That’s a good thing, said Alex Whalen, vice-president of the Atlantic Institute for Market Studies, a Halifax-based think-tank that supports reducing government spending.

“I don’t think taxpayer interests would be served by those proposals,” Whalen said. “The concern has to be that there are public dollars involved.”

As a Crown corporation, Canada Post is required to be financially self-sustaining. With more than 60,000 employees, the company made a pre-tax profit of $74 million in 2017, largely due to increased parcel delivery thanks to Amazon, according to its financial statements. Investing in projects outside of its core mandate of delivering mail could jeopordize its profitability, Whalen said.

“If there were good returns in this kind of business, the private sector would already be doing it,” Whalen said of the proposed postal bank. “If the union thinks this is a great idea, are they going to be an investor in the bank?”

Pension financing?

To finance the union’s proposals, there is one obvious source of funds outside of asking taxpayers or the company: workers’ pensions.

With about $25 billion under management, stocks in the big Canadian banks and oil companies — some of the very industries the union’s proposals are trying to tackle — make up some of the largest investments for postal workers’ pensions, according to 2017 financial statements.

The workers, however, have no say over how their pensions are invested, Paleck said. “We have no decision-making power whatsoever.”

That situation isn’t unusual for Canadian workers, said Tessa Hebb, a researcher at Carleton University’s Centre for Community Innovation who specializes in responsible investing.

“Some representation from employees would be really beneficial, both for the positive components for adjusting to a low-carbon economy and also for the basic protections for workers,” from bad decisions by pension fund managers, she said.

However, she cautions against the idea of using pension funds from CUPW to finance new initiatives at Canada Post like the postal bank or green retrofit.

“You don’t want the pension funds to be constrained in investing in their own business,” Hebb said. “The legal term for that is self-dealing.”

Such moves have often hurt workers when the companies themselves face financial trouble and look to their employees’ pension funds as a source of capital, she said, citing the examples of Sears and Nortel Networks.

In the U.S., pensions under union control — or funds jointly managed by workers and management — have made a series of profitable investments in green technologies or urban renewal projects like affordable housing, she said. And there’s no reason why similar successes couldn’t be replicated in Canada.

“Ten years ago, if you were a pension fund in California and you were an early investor in Tesla, you certainly made your money back and then some,” Hebb said. “The shift to a low-carbon economy is going to bring forward some really interesting investment opportunities.”