Four Indigenous teenagers, inspired by their remote community home in WA’s Pilbara, are using their school holidays to create a futuristic world with a new virtual reality film titled Future Dreaming.

Alison Lockyer, Maverick Eaton, Nelson and Max Coppin from Roebourne are no strangers to technology.

When they were just 10 and 11 years old, like most kids, drawing comics was just a typical pastime growing up in the bush.

In 2012, the four were among a group of 40 kids from the community that created an interactive digital comic, NEOMAD.

Set in the red ochre foothills of Murujuga within the Burrup Peninsular, it follows the fantasy adventures of the Love Punks and the Satellite Sisters.

They are two groups of young heroes — one keeps an eye on ‘country’ from outer space, and the other roams with rangers in a digitised desert full of spy bots, magic crystals, fallen rocket boosters, and mysterious petroglyphs.

At its core the comic is a space opera, but it is clear the kids draw their inspiration from their land and culture.

Since launching NEOMAD, the comic has travelled to cities around the world such as Seoul, Los Angeles and Lodz in Poland.

With the assistance of arts and cultural development organisation Big hART’s Yijala Yala Project, the children then created short films enacting their adventures from the NEOMAD comics.

It has since caught the attention of national broadcasters.

Now 16 and 17 years old, the four teenagers along with the Roebourne community are now in talks with the ABC and NITV for a live-action television series adaptation.

From digital screens to virtual reality

Since NEOMAD, the four have taken their skills in animation, graphic design, photoshop, scriptwriting, sound recording and filmmaking to the realms of virtual reality cinematography and motion sensor technology.

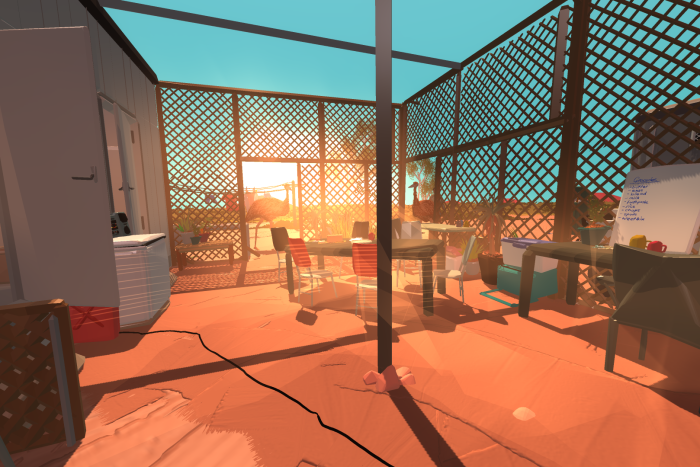

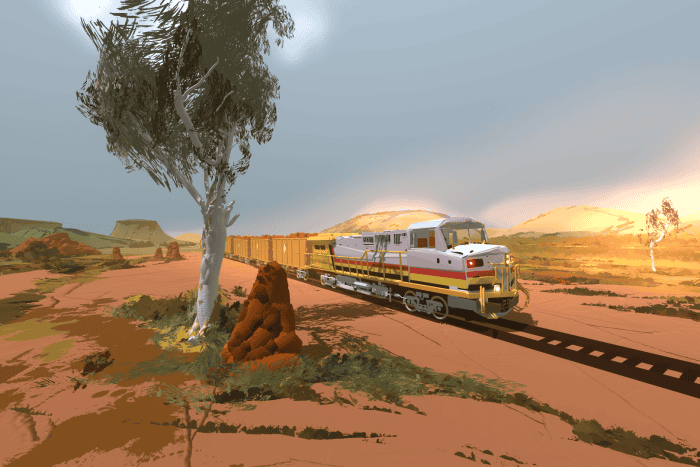

The teenagers have created immersive worlds or ‘stories’ set in the future within a new virtual reality film, Future Dreaming.

Using Google’s Tilt Brush, they slowly paint their world from within.

Alison Lockyer said their stories were set decades into the future.

“Our stories go for one week, five years, 10 years, 20 years into the future,” she said.

Maverick Eaton created his world based from his nan’s block in the remote Pilbara station of Pippingarra.

“I feel proud of myself. If I ever have kids I’d show them this.”

Nelson Coppin visualised his world depicting the Pilbara landscape of red dust, spinifex and ghost gums with trains carrying iron ore traversing across his traditional homeland.

Max Coppin said it was the first time this technology had been available in the Roebourne community.

“Getting to know the paintbrushes, the tools, drawing your own design, all these weird and cool things that are in there that you need to be able to learn before doing new projects,” he said.

“Being able to have access to these technologies living in remote communities is great and it shows what young kids can do.”

Max said virtual reality was a different way of storytelling but he identified it as part of his own cultural legacy.

Building futures and future building

Mentor Stu Campbell from the Yijala Yala Project worked with the teenagers throughout the years from NEOMAD to the Future Dreaming projects.

“The core of our work is trying to figure out exciting opportunities for young people but also career paths and trajectories, experiences that can be part of their CV,” he said.

Mr Campbell said he had learnt a lot throughout the years working with young people in Roebourne.

“I learned the nuances of the young people, they would say things in different ways than I would, those are the kind of things that gives this place its unique character,” he said.

“All the cultural stories from around here, they talk of the big snake that lives under the post office, the Wahlu [Dreamtime serpent]. That’s obviously not something that lived under my post office where I grew up in Tasmania.”

He said it was one way the thousands of years of cultural heritage and storytelling associated with the area was now being interpreted using contemporary tools.

“If you do include those cultural references, then you have to get the elders involved to give you permission to be able to reference those ancient and sacred stories,” Mr Campbell said.

“That creates another interesting creative workshop, where the elders are teaching the young people about the area but also the young people explaining to the elders how they plan to present the story using the technology

“It’s a really nice correlation with what we’re trying to do with the kids, to have a dream about what their future vision would look like and come into the virtual reality workshop and paint their vision.”

Mr Campbell said it was important that the kids had an active role in realising their futures and that their future building was a shared experience.

“There is a big history of storytelling and artmaking in the community, and the elders can really support that process,” he said.