The prototypes are being exhibited as part of OCAD’s 103rd annual graduation exhibition, GradEx

Scott Hladun wishes his brother had it easier when he was growing up.

Matthew Hladun has autism spectrum disorder, which made it difficult for him to communicate his emotions and often led to him acting out in school.

“He had so much trouble when he was younger and now he lives on his own and has a job and he’s doing really well,” said Hladun. “I believe that that’s because all of the interventions my mom provided him with. I would love to help provide those for other students.”

Hladun is one of two graduating students from OCAD who have unveiled new products to help people with autism interact with the world around them. The designs are part of OCAD’s annual graduation exhibition, GradEx, which includes the work of 900 students. It runs until Sunday.

“When [people with autism] aren’t able to communicate what they want to say, it causes problem behaviours like acting out,” said Hladun, a fourth-year undergraduate student in the Digital Futures program at OCAD.

He’s designed a device called “The Emotional Robot” to help lower-functioning children with autism express themselves better.

Hladun says the robot is meant to be a companion to young children as they navigate school and home life.

“The idea is that it’s going to be something that follows them from their house all the way to school, so it’s the one constant that they have,” said Hladun.

The robot enables children to communicate a variety of messages to teachers, parents or other caregivers.

On its front side is a screen that displays different pictures that are controlled by turning a knob on the side of the robot’s head. The pictures include a toilet, a game controller, and a notebook, among others. Thumbs up and thumbs down pictures allow the user to communicate “yes” and “no.”

The robot also has a camera that uses Google’s machine-learning software to identify whether the child is feeling sad, angry or happy. The robot then responds with different actions based on how the child is feeling.

It lights up to lead children through breathing exercises, flashing lights when they are happy, or notifies others when the child is sad.

“I want to bring a little more artificial intelligence to this robot so that it’s able to tailor itself to each student,” said Hladun.

From the virtual to the physical

Teresa Lee was on a similar track when she designed an augmented reality app for younger adults with autism.

Lee has worked with hundreds of autistic children as a behavioural therapist over the past eight years and now consults with the Toronto District School Board. She’s a graduate student at OCAD in the inclusive design program

In the course of her work, Lee noticed that despite the communication and social challenges people with autism experience, many of them thrive in the virtual environment.

“There was something clearly happening in the virtual world because they’re communicating, they’re socializing,” said Lee.

So Lee connected with three people from different online communities for people with autism.

“They were able to speak to their experiences of the virtual world and how that is different from the physical world,” said Lee. “And what they hope to kind of export into the physical world so they can be successful as well.”

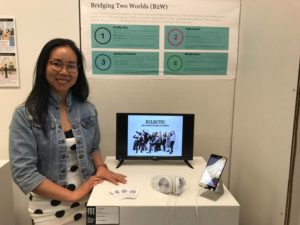

Lee’s mobile app, Bridging 2 Worlds, incorporates these insights.

It’s meant to be used at events where the app is downloaded in advance and populated with personal information about each user. When you hold the camera over a person’s face, it uses facial recognition to provide information about that person. The idea is that going into an interaction with pre-existing knowledge about a person may make it easier to speak to them.

“Oftentimes, autistic people like to go on and on about their special interests. They are very passionate about special interests and that’s how they form their friendships,” said Lee.

Users can also attach icons like a heart to objects in the room that are visible to other users.

Sara Diamond, president of OCAD University said these two examples of inclusive design show it is “in the DNA” of the Digital Futures program at the school.

“How to create support systems that empower and engage people with disabilities and aging populations is a big focus in our undergraduate and graduate programs throughout the school,” said Diamond.