Last November, Intel (NASDAQ: INTC) formally announced that it would be entering the market for stand-alone graphics processors, a market that it hasn’t participated in for nearly two decades.

Intel has many years of experience in building graphics processors, but these processors have been designed exclusively to be embedded into the company’s microprocessors.

Although these integrated graphics processors have seen performance and feature improvements over the years, they are generally regarded as inadequate for running modern 3D games at reasonable-quality settings and acceptable performance.

Since the market for gaming-oriented stand-alone (or discrete) graphics processors is growing, and since discrete graphics processors are relatively high-value pieces of silicon, it’s only natural that Intel would want to build higher-performance stand-alone graphics processors based on the technology that it already develops for integration into its processors.

In this column, I’d like to offer some thoughts on what would constitute success for Intel’s efforts in discrete graphics.

The goal for Intel

Ultimately, Intel’s goal with respect to discrete graphics is to try to increase the average amount of revenue that it generates from personal computers. From a financial perspective, Intel’s stand-alone graphics processor market will be successful if its efforts here ultimately lead to a meaningful increase in its processor average selling prices.

Not every personal computer with an Intel processor will use discrete graphics (for many consumer and business use cases, Intel’s standard integrated graphics are more than sufficient), but the market for computers with stand-alone graphics processors is reasonably large and growing — although a decent portion of that growth may be due to a potentially unsustainable boom in cryptocurrency production.

The market is probably large enough to be interesting to Intel, and considering that Intel has a tremendous amount of influence in the personal computer industry and deep relationships with the major computer makers, the company has a real opportunity to make inroads in certain portions of the market for stand-alone graphics processors.

Baby steps

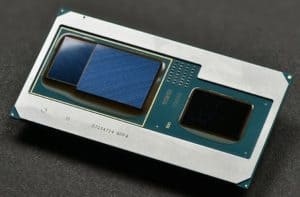

Intel recently announced a processor that incorporates a last-generation Intel-designed processor with a third-party graphics processor on a single silicon package. The part is aimed at relatively thin and light gaming-oriented laptop computers.

The first step for Intel will likely be to replace the third-party graphics processor with an in-house design in future iterations of the part. By moving to its own graphics processor design in such an integrated package, Intel can more tightly integrate the processor and the graphics processor, which could lead to performance and/or power efficiency benefits.

From a financial perspective, Intel would be able to meaningfully improve its profit margins per unit (or offer a product at a lower price while maintaining the same margins) since it would no longer need to pay a third party for a relatively high-value chip to build the integrated product.

Intel’s next step would be to try to win significant, high-volume notebook and all-in-one computer designs with such products. Candidates for such a chip could be products like the Surface Book and Surface Studio, the MacBook Pro and iMac product lines — high-end devices that currently use stand-alone graphics processors but could potentially benefit from a more compact, single-package part.

Should Intel succeed in gaining traction in high-volume systems with parts that combine a stand-alone graphics processor and a CPU on a single package, then Intel could try building specific graphics processors targeted at the gaming desktop computer market as part of add-in-boards.

For Intel to have a chance of successfully competing here, it would probably need to build higher-performance chips than what it would sell as something connected on-package to a CPU, requiring additional product development and marketing costs (as the go-to-market strategy for add-in-boards is different from that of selling chips directly to system makers).

However, considering that a significant portion of the revenue and gross profit margin dollars available in the stand-alone graphics processor market are to be had in the gaming-oriented desktop computer add-in-card market, Intel would likely want to expand its efforts there in the future — if it can find success in the gaming notebook and all-in-one desktop markets with its more integrated solutions.